- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

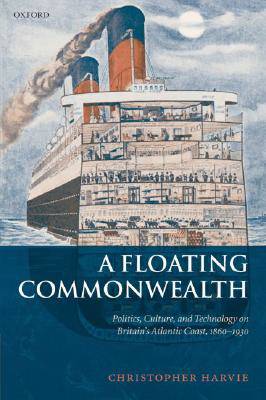

A Floating Commonwealth

Politics, Culture, and Technology on Britain's Atlantic Coast, 1860-1930

Christopher T Harvie

Livre relié | Anglais

209,45 €

+ 418 points

Description

Christopher Harvie offers a new portrait of society and identity in high industrial Britain by focusing on the sea as connector, not barrier. Atlantic and 'inland sea' together, Harvie argues, created a "floating commonwealth" of port cities and their hinterlands whose interaction, both with one another and with nationalist and imperial politics, created an intense political and cultural synergy. At a technical level, this produced the freight steamer and the efficient types of railways which opened up the developing world, as well as the institutions of international finance and communications in the age of "telegrams and anger". And ultimately, the resources of the Atlantic cities, their shipyards and works, enabled Britain to win withstand the test of the First World War. Meanwhile, as Harvie shows, the continuous attempt to make sense of an ever-changing material reality also stimulated the discourses on which social criticism and literary modernism were based, from Carlyle to James Joyce -- although the ultimate outcome, of slump and emigration, would leave enduring problems in the years to come.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 336

- Langue:

- Anglais

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780198227830

- Date de parution :

- 02-06-08

- Format:

- Livre relié

- Format numérique:

- Genaaid

- Dimensions :

- 157 mm x 234 mm

- Poids :

- 657 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.