Vous voulez être sûr que vos cadeaux seront sous le sapin de Noël à temps? Nos magasins vous accueillent à bras ouverts. La plupart de nos magasins sont ouverts également les dimanches, vous pouvez vérifier les heures d'ouvertures sur notre site.

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Vous voulez être sûr que vos cadeaux seront sous le sapin de Noël à temps? Nos magasins vous accueillent à bras ouverts. La plupart de nos magasins sont ouverts également les dimanches, vous pouvez vérifier les heures d'ouvertures sur notre site.

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

83,95 €

+ 167 points

Description

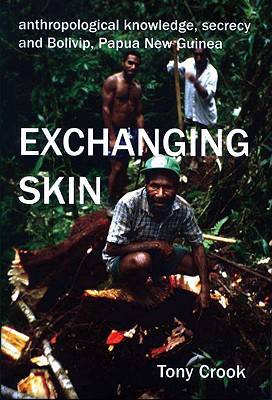

The Min peoples of Papua New Guinea are renowned for their secret male initiation rituals and have proven to be one of the most enigmatic cultures in anthropological experience. This study analyses the 'Min problem', and argues that the root of this long-standing interpretative impasse has been in Anthropology's view of secrecy and knowledge. Because Barth's pioneering work in this small corner of Melanesia still exerts an important influence on the discipline's contemporary view of knowledge, the implications of this critique go far beyond a little known problem and raise fundamental questions about the nature of anthropological knowledge itself. In Bolivip, knowledge-making is perceived as exchanging skin and bodily resources with others, and is withheld until a person is capable of bearing it. The argument uses these understandings to consider our own assumptions, and works through alternating chapters. An imagistic ethnography of Bolivip with vivid descriptions of life in the rainforest, supported by high quality illustrations, describes how arboreal and horticultural metaphors motivate the growth of persons and plants. These chapters alternate with ethnographies of anthropological knowledge proposing new readings of Melanesianist texts by Mead, Bateson and Fortune; Weiner and Strathern; and Barth. Having suggested that the root of the Min problem also underpins a wider impasse in anthropological knowledge, the study concludes with a new analytical figure, 'the textual person', that suggests a more promising future for anthropological knowledge.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 230

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780197264003

- Date de parution :

- 11-11-07

- Format:

- Livre relié

- Format numérique:

- Genaaid

- Dimensions :

- 167 mm x 237 mm

- Poids :

- 712 g