- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

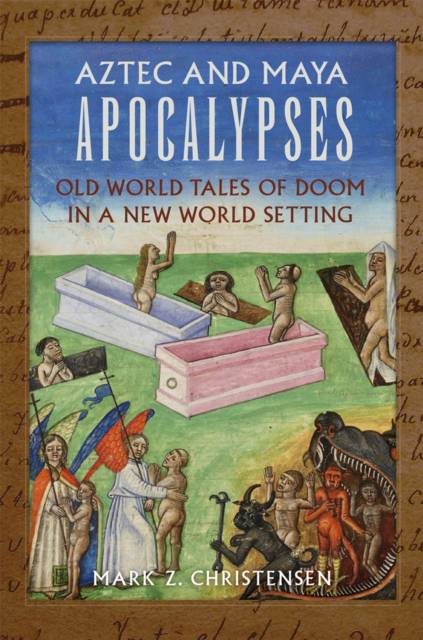

Aztec and Maya Apocalypses

Old World Tales of Doom in a New World Setting

Mark Z Christensen

Livre relié | Anglais

93,45 €

+ 186 points

Description

The Second Coming of Christ, the resurrection of the dead, the Final Judgment: the Apocalypse is central to Christianity and has evolved throughout Christianity's long history. Thus, when ecclesiastics brought the Apocalypse to Indigenous audiences in the Americas, both groups adapted it further, reflecting new political and social circumstances. The religious texts in Aztec and Maya Apocalypses, many translated for the first time, provide an intriguing picture of this process--revealing the influence of European, Aztec, and Maya worldviews on portrayals of Doomsday by Spanish priests and Indigenous authors alike. The Apocalypse and Christian eschatology played an important role in the conversion of the Indigenous population and often appeared in the texts and sermons composed for their consumption. Through these writings from the sixteenth to the early nineteenth century--priests' "official" texts and Indigenous authors' rendering of them--Mark Z. Christensen traces Maya and Nahua influences, both stylistic and substantive, while documenting how extensively Old World content and meaning were absorbed into Indigenous texts. Visions of world endings and beginnings were not new to the Indigenous cultures of America. Christensen shows how and why certain formulations, such as the Fifteen Signs of Doomsday, found receptive audiences among the Maya and the Aztec, with religious ramifications extending to the present day. These translated texts provide the opportunity to see firsthand the negotiations that ecclesiastics and Indigenous people engaged in when composing their eschatological treatises. With their insights into how various ecclesiastics, Nahuas, and Mayas preached, and even understood, Catholicism, they offer a uniquely detailed, deeply informed perspective on the process of forming colonial religion.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 252

- Langue:

- Anglais

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780806190358

- Date de parution :

- 14-07-22

- Format:

- Livre relié

- Format numérique:

- Genaaid

- Dimensions :

- 152 mm x 229 mm

- Poids :

- 544 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.