- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

This thesis seeks to establish a connection between abstract thought and material practice. It does so by focusing on the relation between the transcendental philosophy of time and the socio-technics of timekeeping practices.

The thesis begins with a discussion of Kant's philosophy of time as outlined in the Critique of Pure Reason. It argues that Kant's discovery of the transcendental coincides with the development of an entirely new conception of time. This new conception overturns classical thought by making a distinction between the abstract form of time and the empirical phenomena of movement and change.

The second chapter maps the transcendental philosophy of time on to the history of capitalist timekeeping. This history includes the invention and development of the mechanical clock, temporal standardization, and the increasing importance of the equation 'time = money.' The aim in bringing these two spheres together is to show both that Kant's philosophy of time owes much to his empirical surroundings, and also that capitalist time can only be understood through the temporal abstraction of transcendental thought. This link between Kant and capitalism is blocked, however, by a dividing line which separates the philosophical nature of time from the empirical changes of history.

In order to surpass this problem, the thesis turns to the work of Deleuze and Guattari whose 'transcendental materialism' connects the abstract production of time with empirical innovations. This is accomplished by replacing the classical conception of a transcendent eternity with the immanent materiality of an exterior plane. This plane-which they call Aeon and is composed of thresholds, or singular events-makes no distinction between time and that which occurs in time. The final chapter explores the dawn of the third millennium-or Y2K-as constituting one such Aeonic eventSpécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 200

- Langue:

- Anglais

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

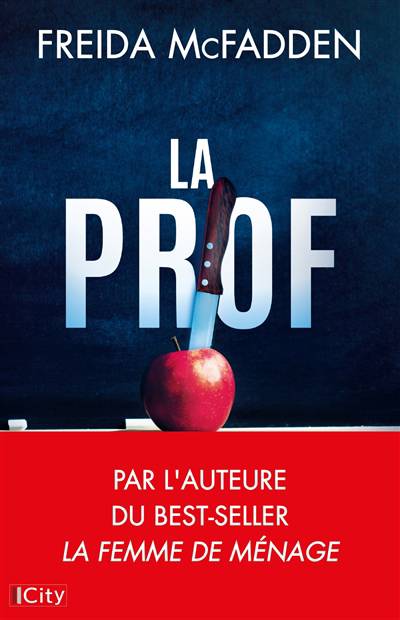

- 9781778154904

- Date de parution :

- 13-01-23

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 152 mm x 229 mm

- Poids :

- 272 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.