- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

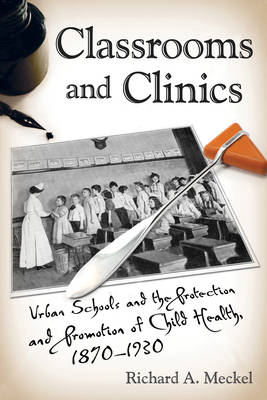

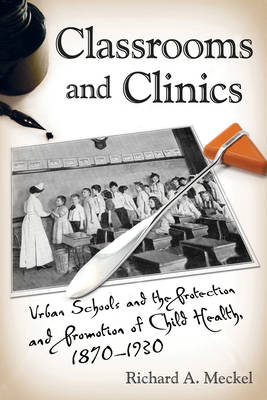

Classrooms and Clinics

Urban Schools and the Protection and Promotion of Child Health, 1870-1930

Richard a MeckelDescription

Classrooms and Clinics is the first book-length assessment of the development of public school health policies from the late nineteenth century through the early years of the Great Depression. Richard A. Meckel examines the efforts of early twentieth-century child health care advocates and reformers to utilize urban schools to deliver health care services to socioeconomically disadvantaged and medically underserved children in the primary grades. Their goal, Meckel shows, was to improve the children's health and thereby improve their academic performance.

Meckel situates these efforts within a larger late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century public discourse relating schools and schooling, especially in cities and towns, to child health. He describes and explains how that discourse and the school hygiene movement it inspired served as critical sites for the constructive negotiation of the nature and extent of the public school's-and by extension the state's-responsibility for protecting and promoting the physical and mental health of the children for whom it was providing a compulsory education.

Tracing the evolution of that negotiation through four overlapping stages, Meckel shows how, why, and by whom the health of schoolchildren was discursively constructed as a sociomedical problem and charts and explains the changes that construction underwent over time. He also connects the changes in problem construction to the design and implementation of various interventions and services and evaluates how that design and implementation were affected by the response of the civic, parental, professional, educational, public health, and social welfare groups that considered themselves stakeholders and took part in the discourse. And, most significantly, he examines the responses called forth by the question at the heart of the negotiations: what services are necessitated by the state's and school's taking responsibility for protecting and promoting the health and physical and mental development of schoolchildren. He concludes that the negotiations resulted both in the partial medicalization of American primary education and in the articulation and adoption of a school health policy that accepted the school's responsibility for protecting and promoting the health of its students while largely limiting the services called for to the preventive and educational.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 272

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780813562407

- Date de parution :

- 07-11-13

- Format:

- Livre relié

- Format numérique:

- Genaaid

- Dimensions :

- 152 mm x 229 mm

- Poids :

- 562 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.