- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

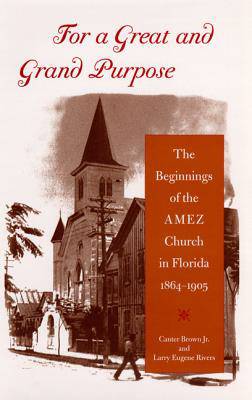

For a Great and Grand Purpose

The Beginnings of the Amez Church in Florida, 1864-1905

Edgar Canter Brown, Larry Eugene Rivers

48,95 €

+ 97 points

Description

The story of a church that became influential within the Black community in Florida after the Civil War

This history of the

African Methodist Episcopal Zion (AMEZ) Church in Florida tells how

dedicated members of one of the oldest and most prominent black

religious institutions created a forceful presence within the

African-American community--against innumerable odds and constant

challenges.

established an official presence in the state one year before its

better-known cousin and rival, the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

When Connecticut native Wilbur Garrison Strong arrived in Key West in

1864, he stood out as the first black ordained minister in all of

peninsular Florida. He brought with him the northern Methodist tradition

of joyful praise and preaching, an ethos of a plain and simple gospel

that emphasized "righteous living" and an unbending commitment to

emancipation and hope. With Key West under the control of Union forces

during much of the Civil War, slaves and free Black people were able to

express their desire for independence from white churches more easily

there than throughout the rest of the state, and they gravitated to the

church that Strong established. During its formative years, the

AMEZ became one of the first mainline churches to ordain women to full

clerical status. Its ministers commanded great strength in certain

cities, and its membership included more of the urban and middle-class

population than was typical for southern religious organizations, which

were predominantly rural. At its zenith, the AMEZ was one of the largest

African-American churches in the state. But it faced

difficulties--gender issues, idiosyncratic leadership, rivalries between

local ministers and Episcopal authorities, and political dissension at a

point when the church was attempting to address larger social issues.

In addition, the scourge of hurricanes and yellow fever and citrus crop

freezes affected church fortunes. By 1905, when the governor urged the

expulsion of all African-Americans from Florida and when state laws

mandated racial segregation on public transportation, the era of

lynching, discrimination, and disfranchisement already had begun and the

period of AMEZ decline had commenced. In this remarkable yet

virtually unknown story, the coauthors capture the mood of the

post-Civil-War period in Florida, when Black people faced the obstacles

and the opportunities that accompanied their new freedom. This work adds

significantly to the growing body of literature on African-Americans in

Florida and offers keen insights into the nature of institution

building within the black community and the greater society.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 272

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780813027784

- Date de parution :

- 27-10-04

- Format:

- Livre relié

- Format numérique:

- Genaaid

- Dimensions :

- 164 mm x 232 mm

- Poids :

- 539 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.