- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

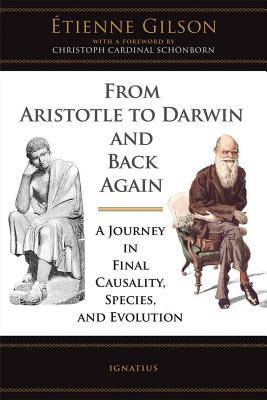

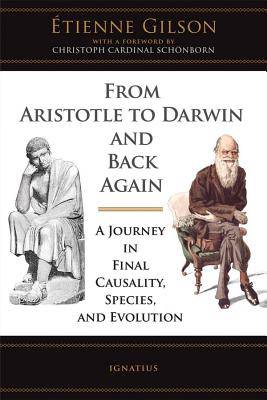

From Aristotle to Darwin and Back Again

A Journey in Final Causality, Species, and Evolution

Etienne GilsonDescription

Darwin's theory of evolution remains controversial, even though most scientists, philosophers, and even theologians accept it, in some form, as an explanation for the variety of organisms. The controversy erupts when the theory is used to try to explain everything, including every aspect of human life, and to deny the role of a Creator or a purpose to life.

The overreaching of many scientists into matters beyond the self-imposed limits of scientific method is perhaps explained in part by the loss of two important ideas in modern thinkingùfinal causality or purpose, and formal causality. Scientists understandably bracket the idea out of their scientific thinking because they seek explanations on the level of material and efficient causes only. Yet many of them wrongly conclude from their selective study of the world that final and formal causes do not exist at all and that they have no place in the rational study of life. Likewise, many erroneously assume that philosophy cannot draw upon scientific findings, in light of final and formal causality, to better understand the world and man.

The great philosopher and historian of philosophy, Etienne Gilson, sets out to show that final causality or purposiveness and formal causality are principles for those who think hard and carefully about the world, including the world of biology. Gilson insists that a completely rational understanding of organisms and biological systems requires the philosophical notion of teleology, the idea that certain kinds of things exist and have ends or purposes the fulfillment of which are linked to their naturesùin other words, formal and final causes. His approach relies on philosophical reflection on the facts of science, not upon theology or an appeal to religious authorities such as the Church or the Bible.

"The object of the present essay is not to make of final causality a scientific notion, which it is not, but to show that it is a philosophical inevitability and, consequently, a constant of biophilosophy, or philosophy of life. It is not, then, a question of theology. If there is teleology in nature, the theologian has the right to rely on this fact in order to draw from it the consequences which, in his eyes, proceed from it concerning the existence of God. But the existence of teleology in the universe is the object of a properly philosophical reflection, which has no other goal than to confirm or invalidate the reality of it. The present work will be concerned with nothing else: reason interpreting sensible experienceùdoes it or does it not conclude to the existence of teleology in nature?"

Etienne Gilson

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 254

- Langue:

- Anglais

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9781586171698

- Date de parution :

- 28-10-09

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 163 mm x 231 mm

- Poids :

- 385 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.