- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

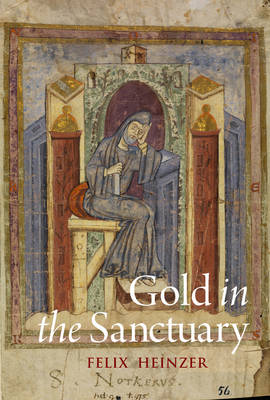

As Peter Dronke observed in his seminal book on the subject, the first heights of achievement in medieval lyric in the Latin West associated with Gottschalk of Orbais (d. ca. 869) and, even more so, with Notker of St Gall, occur in the religious mode, in the second generation after Charlemagne, more than two and a half centuries before secular and vernacular lyrics survive in any abundance. Ironically, it would be religious authority again that in the late sixteenth century would decide the fate of Notker's Liber Ymnorum by banning the singing of sequences from liturgical chant. Indeed, the criticism that emerged in the wake of both the Tridentine Council and the Protestant Reformation recalls Notker's own awareness of the objections, particularly virulent in the west-Frankish realm, leveled against poetical additions to an established chant repertory overwhelmingly based on biblical texts.

The first part of this study is thus dedicated to the strategies Notker adopted to legitimize his endeavor, while attempting to navigate the faultline between scriptural tradition and poetical adornment, between cult and culture. His decision to emulate the structure of Old Testament poetry, especially the Psalms, instead of following the well-worn track of earlier Christian poetry that cleaved to classical metrical schemes, remains fundamental. The second part focuses on Notker's reception, in particular on the posthumous idealization of the stammering poet as a charismatic author, but it also draws attention to the promotion of his work as an undisputed part of liturgical practice up to early modern times.

A meticulous reading of Notker's texts and their backgrounds, as well as the exploration of their multifaceted reverberation in literature and art, allow for retracing the story of a significant if forgotten aspect of the poetic tradition in the Latin Middle Ages.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 322

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780888442284

- Date de parution :

- 15-04-22

- Format:

- Livre relié

- Format numérique:

- Genaaid

- Dimensions :

- 150 mm x 226 mm

- Poids :

- 417 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.