- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

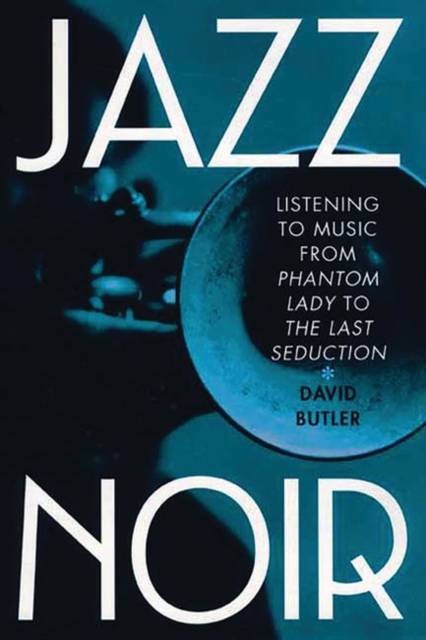

Jazz Noir

Listening to Music from Phantom Lady to the Last Seduction

David ButlerDescription

Jazz has been associated with crime and immorality since early forms of the music were heard in the brothels of New Orleans and the gangster-owned clubs of the 1920s. This association encouraged the use of jazz in film noir, a genre preoccupied with tales of anxiety and urban decay, which flourished in American cinema during the postwar period. Yet, although the extent and nature of this collaboration has often been alluded to, it has rarely been examined in detail. Making significant use of archival sources and documentation, Jazz Noir seeks to correct this oversight, placing the films discussed in their proper historical context and utilizing an interdisciplinary approach that gives equal weight to the films--including such notables as Phantom Lady, I Want to Live!, and Taxi Driver--and to the indelible music that accompanied them.

In so doing, it corrects a great many misunderstandings about this complex, ideologically tinged relationship. Television noirs of the 1950s and 1960s, as well as the cinematic neo-noirs of the 1990s, have used jazz and jazz-flavored music extensively, thus giving rise to the misconception that the genre and the musical style were always intertwined. But as author David Butler reveals, it was only when modern jazz had a number of prominent white exponents that it gained any kind of exposure in Hollywood cinema, and even then such exposure was limited. Nevertheless, the broad range of jazz styles was well suited to the broad range of films noir, and the historical approach Butler takes gives due weight to such considerations. The film noir of the 1940s are as different from the film noir of the 1950s as the jazz of the 1940s is from the jazz of the 1950s, and Jazz Noir provides a unique and valuable study of a rich aesthetic synergy.Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 256

- Langue:

- Anglais

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780275973018

- Date de parution :

- 30-03-02

- Format:

- Livre relié

- Format numérique:

- Genaaid

- Dimensions :

- 166 mm x 238 mm

- Poids :

- 530 g