- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

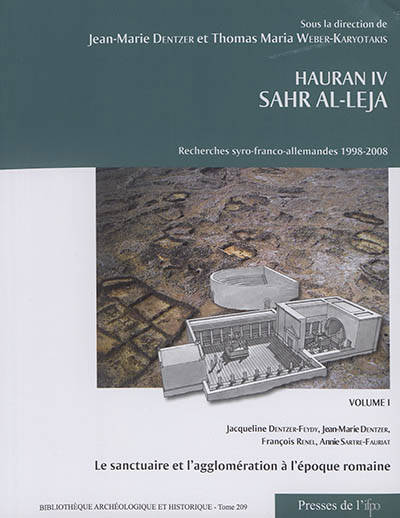

Le sanctuaire et l'agglomération à l'époque romaine

Description

Depuis le début des explorations archéologiques au début du XXe siècle, Sahr, situé dans la partie nord du désert basaltique du Leja (Syrie du Sud), a paru énigmatique : isolé et peu accessible, ce site n'a pas la structure habituelle d'un village. Un sanctuaire, constitué d'un temple au fond d'une cour à portiques et flanqué d'un petit théâtre, occupe la partie centrale de l'agglomération. Celle-ci comporte une cinquantaine d'unités d'habitation composées de pièces couvertes à l'intérieur d'enclos fermés. Ces pièces, souvent organisées en ensembles mitoyens, ne sont pas fermées, dans leur majorité, mais ouvertes sur l'enclos par une large baie ou par un portique. Ces unités d'habitation ne paraissent pas avoir été construites suivant un plan d'organisation du site. Le sanctuaire, en revanche, de même que le théâtre, semblent bien avoir été conçus suivant un même programme. Contrairement aux restitutions de Butler, cette étude prouve qu'un large adyton voûté s'ouvrait au fond de la cella du temple, suivant un schéma bien attesté dans le domaine cultuel syrien, et qu'un autel maçonné était situé à l'intérieur de la cella. Dans la cour à portiques du sanctuaire était construit un podium qui portait un important groupe sculpté à symbolique religieuse et politique dont Th. M. Weber-Karyotakis a fait l'étude (Hauran IV, vol. 2, 2009). Cet état du sanctuaire date de l'époque d'Agrippa II. Il succède à un premier état partiellement conservé datable du milieu du Ier s. av. J.-C.

Ce site ne semble pas avoir bénéficié d'une occupation permanente, mais plutôt d'une occupation saisonnière, sans doute liée aux activités pastorales de populations qui se déplaçaient en fonction des ressources. À ces cycles étaient associées des fêtes religieuses qui donnaient lieu à des rassemblements et des célébrations dans le sanctuaire, le théâtre et les constructions de l'agglomération. L'occupation principale de Sahr al-Leja s'est prolongée du milieu du Ier s. av. J.-C. jusqu'à son abandon presque complet dans la deuxième moitié du IIIe siècle, qui fut suivi d'installations limitées jusqu'à l'époque médiévale.

Sahr, located in the northern part of the basalt desert of the Leja (southern Syria), has been an enigma since the first archaeological explorations in the early 20th century: isolated and difficult of access, this site does not look like a normal village. A sanctuary, composed of a temple at the back of a porticoed courtyard and flanked by a small theatre, lies in the centre of a village consisting of about fifty housing units composed of covered rooms in enclosed compounds. These rooms, often arranged in adjoining groups, are generally not closed, but rather, they open onto the enclosure through a wide bay or a portico. These housing units do not appear to have been built according to any kind of site plan. On the other hand, both the sanctuary and the theatre seem to have been conceived as one project. In contrast with Butler's reconstructions, this study shows that there was a large, vaulted adyton at the back of the temple cella, following a layout that is well-attested in Syrian cultic buildings, and that a masonry altar was located inside the cella. In the porticoed courtyard of the sanctuary there was a podium that bore an important group of religiously and politically symbolic sculptures, which have been studied by T. M. Weber-Karyotakis (Hauran IV, vol. 2, 2009). That stage of the sanctuary dates to the period of Agrippa II. It followed an earlier, but only partially preserved, stage dated to the mid-1st century BC.

This site does not seem to have been permanently occupied, but rather, a seasonal occupation was no doubt linked to the pastoral activities of people who moved according the resources available. Religious festivals were associated to this cycle, which provided a reason for gatherings and celebrations in the sanctuary, the theatre and the buildings of the settlement. The main occupation at Sahr al-Leja stretches from the mid-1st century BC until its near total abandonment in the second half of the 3rd century AD; a small number of buildings continued until medieval times.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 473

- Langue:

- Français

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9782351597293

- Date de parution :

- 04-05-17

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Dimensions :

- 220 mm x 280 mm

- Poids :

- 1800 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.