- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

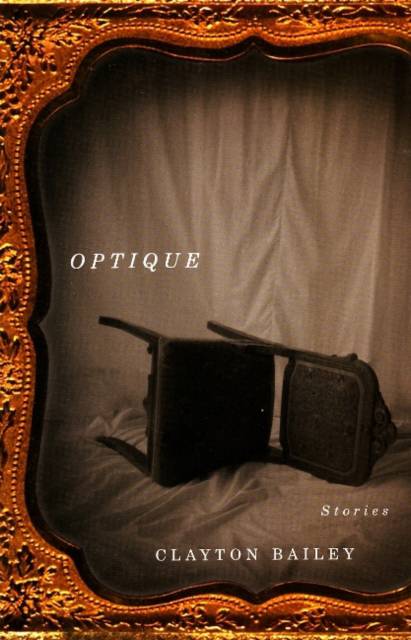

Each story in Clayton Bailey's Optique pivots around an intense emotional relationship with a photograph. From drugstore-developed snapshots to formal portraits, the pictures are all of people, an absent you obsessively pursued through the viewfinder of Bailey's unsettling prose. Often talismans against the violent pain of displacement, ultimately each image and each story reaffirms the eternal capacity of the photograph-and photography's splendid consort, light--to expose the intricacies of the human soul.

The images in the stories span a century and a half-from digital to daguerreotype. In one story, a woman and a man, the possibility of love in the air, separate after discovering harsh pornography on a camera's memory card. In another, a girl watches her brother drown through the crystal-clear ice of a frozen river; his last act is to look at the photograph of his son he keeps in his breast pocket. A soldier in a civil war has a daguerreotypist make a double exposure of him in his dead twin's uniform so their mother will think they are both alive.Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 180

- Langue:

- Anglais

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9781550652147

- Date de parution :

- 01-10-06

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 140 mm x 215 mm

- Poids :

- 299 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.