- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

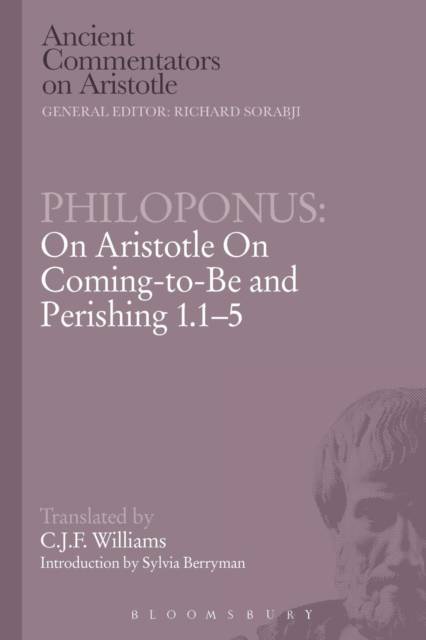

The first five chapters of Aristotle's De Generatione et Corruptione distinguish creation and destruction from mere qualitative change and from growth. They include a fascinating debate about the atomists' analysis of creation and destruction as due to the rearrangement of indivisible atoms. Aristotle's rival belief in the infinite divisibility of matter is explained and defended against the atomists' powerful attack on infinite divisibility.

But what inspired Philoponus most in his commentary is the topic of organic growth. How does it take place without ingested matter getting into the same place as the growing body? And how is personal identity preserved, if our matter is always in flux, and our form depends on our matter? If we do not depend on the persistence of matter why are we not immortal? Analogous problems of identity arise also for inanimate beings.

Philoponus draws out a brief remark of Aristotle's to show that cause need not be like effect. For example, what makes something hard may be cold, not hard. This goes against a persistent philosophical prejudice, but Philoponus makes it plausible that Aristotle recognized this truth.

These topics of identity over time and the principles of causation are still matters of intense discussion.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 240

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9781780938691

- Date de parution :

- 10-04-14

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 156 mm x 234 mm

- Poids :

- 294 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.