Vous voulez être sûr que vos cadeaux seront sous le sapin de Noël à temps? Nos magasins vous accueillent à bras ouverts. La plupart de nos magasins sont ouverts également les dimanches, vous pouvez vérifier les heures d'ouvertures sur notre site.

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Vous voulez être sûr que vos cadeaux seront sous le sapin de Noël à temps? Nos magasins vous accueillent à bras ouverts. La plupart de nos magasins sont ouverts également les dimanches, vous pouvez vérifier les heures d'ouvertures sur notre site.

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

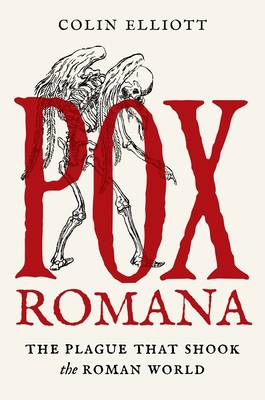

A wide-ranging and dramatic account of the Antonine plague, the mysterious disease that struck the Roman Empire at its pinnacle

In the middle of the second century AD, Rome was at its prosperous and powerful apex. The emperor Marcus Aurelius reigned over a vast territory that stretched from Britain to Egypt. The Roman-made peace, or Pax Romana, seemed to be permanent. Then, apparently out of nowhere, a sudden sickness struck the legions and laid waste to cities, including Rome itself. This fast-spreading disease, now known as the Antonine plague, may have been history's first pandemic. Soon after its arrival, the Empire began its downward trajectory toward decline and fall. In Pox Romana, historian Colin Elliott offers a comprehensive, wide-ranging account of this pivotal moment in Roman history. Did a single disease--its origins and diagnosis still a mystery--bring Rome to its knees? Carefully examining all the available evidence, Elliott shows that Rome's problems were more insidious. Years before the pandemic, the thin veneer of Roman peace and prosperity had begun to crack: the economy was sluggish, the military found itself bogged down in the Balkans and the Middle East, food insecurity led to riots and mass migration, and persecution of Christians intensified. The pandemic exposed the crumbling foundations of a doomed Empire. Arguing that the disease was both cause and effect of Rome's fall, Elliott describes the plague's "preexisting conditions" (Rome's multiple economic, social, and environmental susceptibilities); recounts the history of the outbreak itself through the experiences of physician, victim, and political operator; and explores postpandemic crises. The pandemic's most transformative power, Elliott suggests, may have been its lingering presence as a threat both real and perceived.Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 328

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

- Tome:

- n° 11

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780691219158

- Date de parution :

- 06-02-24

- Format:

- Livre relié

- Format numérique:

- Genaaid

- Dimensions :

- 163 mm x 239 mm

- Poids :

- 680 g