- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

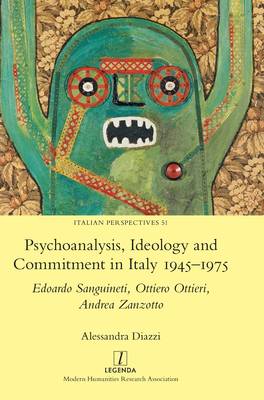

Psychoanalysis, Ideology and Commitment in Italy 1945-1975

Edoardo Sanguineti, Ottiero Ottieri, Andrea Zanzotto

Alessandra DiazziDescription

Over the post-war decades, Italy's 'extroverted' cultural identity was mostly oriented towards social and political questions: the inward turn of psychoanalysis was regarded with suspicion, as a fin-de-siècle cure for middle-class neuroses. The consulting room was, for militant intellectuals, antithetic to class-consciousness and the collective struggle. But despite this resistance from leftist, or Communist, intellectual discourse, psychoanalysis became steadily more influential.

In the period up to the late 1970s, the triad of politics-ideology-commitment acted as a threefold track through which psychoanalysis could spread, and the resistance to it transformed Italy into a unique cultural laboratory for experimental negotiation between analysis and Marxism. Many of these encounters occurred in post-war literature, and Diazzi maps out a distinctively Italian, ideological repurposing of psychoanalysis, turning its inward view into an outward tool of political agency.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 142

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

- Tome:

- n° 51

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9781781887943

- Date de parution :

- 29-08-22

- Format:

- Livre relié

- Format numérique:

- Genaaid

- Dimensions :

- 170 mm x 244 mm

- Poids :

- 430 g