- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

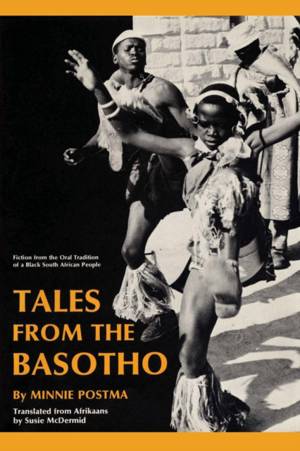

"They say that the eldest of the chief's daughters..." So begins a tale from the Basotho, unfolded by the meager light of a dung fire that burns smokily behind the reed screen sheltering the entrance of the hut. The old ones of the tribe wait until dark before telling their stories, for everyone knows horns will grow from the head of one who tells a story during daylight hours. Tales from the Basotho abounds with elements familiar to folk narrative. The heroes and heroines are the chiefs and their wives, their sons and their daughters. Fantastic creatures frequent the narratives. exhibiting their awful powers.

Rustic peace and beauty pervade the stories, as Minnie Postma amply demonstrates in her versions of the tales. Something fearful may be occurring--the dreaded Koeoko pulling the only son of the chief under water--but, at the same time, girls with babies tied to their backs are searching for edible bulbs in the veld, and an old woman dreams in the gentle sunlight in front of the huts.

These tales from the Basotho are for entertainment only. There is a tabu against telling tales while the sun shines, because daylight hours must be saved for work. The telling itself is the- reason the story exists, for the audience is already aware of the outcome of each tale. As Wm. Hugh Jansen emphasizes in his foreword, "text" and "context" are often easily interpreted and made accessible in a translation, but Tales from the Basotho is ultimately successful for its rendering of "texture." And texture is doubly hard to convey when the telling itself is of primary importance. Minnie Postma and Susie McDermid have transferred the art of the Basotho raconteur onto the printed page. All the simple, understandable formulas, exclamations, and repetitions used so skillfully by the native storyteller are present. Rhythm is an important element in the tales, and a word, a phrase, even a whole paragraph will be repeated until the rhythm satisfies the storyteller, in tum increasing the appreciation of the listeners.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 204

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

- Tome:

- n° 59

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780292737303

- Date de parution :

- 01-01-74

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 152 mm x 229 mm

- Poids :

- 303 g