Vous voulez être sûr que vos cadeaux seront sous le sapin de Noël à temps? Nos magasins vous accueillent à bras ouverts. La plupart de nos magasins sont ouverts également les dimanches, vous pouvez vérifier les heures d'ouvertures sur notre site.

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Vous voulez être sûr que vos cadeaux seront sous le sapin de Noël à temps? Nos magasins vous accueillent à bras ouverts. La plupart de nos magasins sont ouverts également les dimanches, vous pouvez vérifier les heures d'ouvertures sur notre site.

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

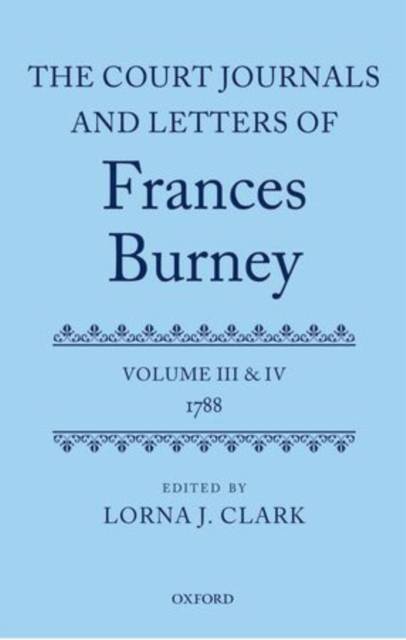

The Court Journals and Letters of Frances Burney

Volume III and IV: 1788

641,95 €

+ 1283 points

Description

The third and forth of six volumes that will present in their entirety Frances Burney's journals and letters from July 1786, when she assumed the position of Keeper of the Robes to Queen Charlotte, to her resignation in July 1791. Burney's later journals have been edited as The Journals and Letters of Fanny Burney (Madame d'Arblay), 1791-1840 (12 vols., 1972-84). Her earlier journals have been edited as The Early Journals and Letters of Fanny Burney (4 vols. to date, 1988- ). The Court Journals and Letters of Frances Burney continues the modern editing of Burney's surviving journals and letters, from 1768 until her death in 1840. 1788 is a crucial year that stands at the heart of the Court Journals and Letters of Frances Burney. Its centrality to Burney's court experience is suggested by the fact that in the first published edition of her Diary and Letters (1842-46) which compressed sixty years' worth of material into seven volumes, it took up almost a whole volume. Yet about a third of the text had been suppressed, either deleted by the elderly author or censored by the editor; moreover, the non-diary letters were completely ignored. All of this suppressed material has been restored and is published here, much of it for the first time. What fascinates readers about the year 1788 are two historic events: the opening of the trial of Warren Hastings and the onset of the 'madness' of George III, which precipitated the Regency Crisis. There were personal crises that affected Burney as well and both facets--public and private--are intertwined in a vivid recreation of everyday life at the Georgian court. The years spent as Keeper of the Robes to Queen Charlotte represent a watershed in Burney's life; separated from family, friends, and the dazzling London assemblies in which she could shine, she was oppressed by the monotonous routine and embarrassed by her position. While initially she tried to accept her fate, eventually she would admit her unhappiness and desire to escape. In this process, 1788 represents a year of transition.It also represents a time of literary experimentation for Burney's suffering was a source of strength that tempered her as a writer, inspiring her to embark on a series of tragedies, and honing her skills in copious accounts of the day's transactions. However, she was often behind-hand in writing up her entries (usually by more than a year), so the text that is presented as a daily journal is often written in hindsight. Though composed in the full knowledge of later events, the narrative is skilfully presented as though written up-to-the-minute. The text contained in these volumes, and the commentary that underlines the double time-scheme, may revolutionise our understanding of Burney's mastery of the epistolary.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 820

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780199688142

- Date de parution :

- 21-10-14

- Format:

- Livre

- Dimensions :

- 154 mm x 221 mm

- Poids :

- 1419 g