- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

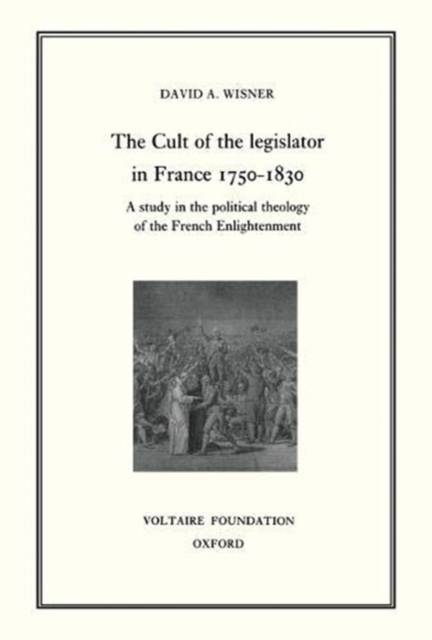

The Cult of the Legislator in France 1750-1830

A Study in the Political Theology of the French Enlightenment

83,95 €

+ 167 points

Description

Historians have long debated the nature of the relationships between the Enlightenment and the French Revolution. This study traces a cultural and doctrinal current from the intellectual revolution of the seventeenth century to 1789, arguing that the contribution of the philosophes to this current had a fundamental bearing on the events of the revolutionary decade.

How might a state in decline reform, in not transform, its constitution? Two generations of French philosophes struggled to answer this question. Their conclusions took the form of a deistic political theology, according to which comprehensive reform had to be the work of an enlightened legislatior. The generation of 1789 inherited this outlook and set about enacting the reforms of their philosophic forefathers. Important to this enterprise was the rich variety of symbolic representations accompanying the theoretical writings of eighteenth-century publicists and activists. Enlightenment historiography, reflecting the reforming tendencies in the writing of the philosophes, included multiple allusions to the figure of the lawgiver in history, all the while looking for improvement. By the 1770s such reform appeared both necessary and imminent. Meanwhile, the various loci of enlightenment sociability took in the air of the 'constitutional arena'. But the philosophes also invested their movement with a variety of religious forms, which complemented the logic of their political theology. Theirs was indeed a cult of the legislator. These varied tendecies crystallised during the early years of the Revolution. The author shows how Frenchmen self-consciously imitated their historic role models as they participated in revolutionary assemblies. A new phase in history seemed to be dawning, one in which goodness would reign supreme. As Hegel put it some decades later, it appeared as if the heavens and the earth had been rejoined. Such sentiments found a central place in Jacques-Louis David's Serment du Jeu de Paume, commissioned in 1790 by the Paris Jacobin Club to hang in the chambers of the National Assembly. In a novel interpretation of David's project, the author demonstrates how his composition wove the strands of the Enlightenment cult of the legislator into a lively canvas in which future generations of French men and women would be confronted with the providentially inspired founding act of the new regime.Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 176

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780729405508

- Date de parution :

- 01-01-97

- Format:

- Livre relié

- Format numérique:

- Genaaid

- Dimensions :

- 164 mm x 240 mm

- Poids :

- 549 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.