- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

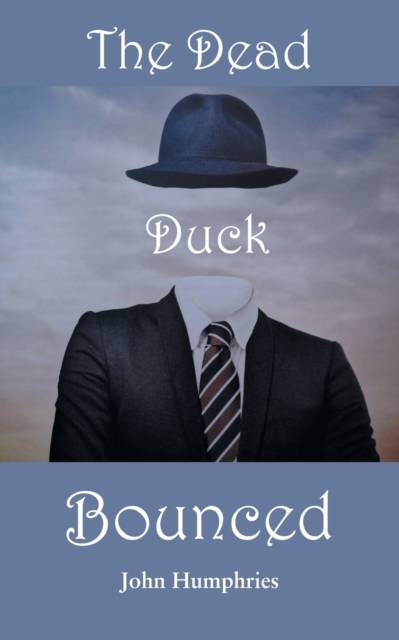

Evidence of a conspiracy at the highest level of the British Security Service is uncovered when a newspaper reporter searches a recently declassified MI5 file. Another Burgess and Maclean defection to Russia or more sinister?

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 312

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9781839758607

- Date de parution :

- 21-04-22

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Dimensions :

- 202 mm x 128 mm

- Poids :

- 346 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.