- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

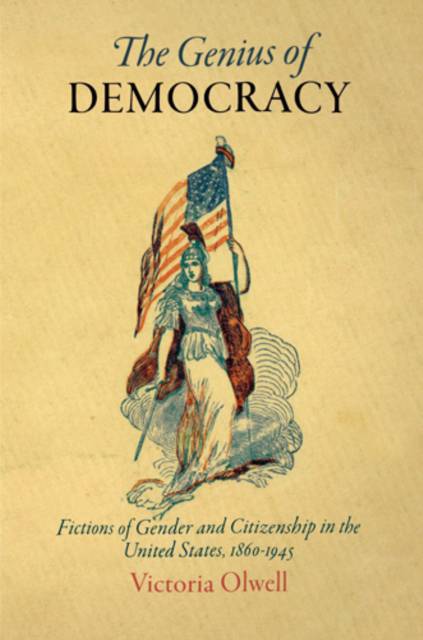

The Genius of Democracy

Fictions of Gender and Citizenship in the United States, 186-1945

Victoria OlwellDescription

In the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century United States, ideas of genius did more than define artistic and intellectual originality. They also provided a means for conceptualizing women's participation in a democracy that marginalized them. Widely distributed across print media but reaching their fullest development in literary fiction, tropes of female genius figured types of subjectivity and forms of collective experience that were capable of overcoming the existing constraints on political life. The connections between genius, gender, and citizenship were important not only to contests over such practical goals as women's suffrage but also to those over national membership, cultural identity, and means of political transformation more generally.

In The Genius of Democracy Victoria Olwell uncovers the political uses of genius, challenging our dominant narratives of gendered citizenship. She shows how American fiction catalyzed political models of female genius, especially in the work of Louisa May Alcott, Henry James, Mary Hunter Austin, Jessie Fauset, and Gertrude Stein. From an American Romanticism that saw genius as the ability to mediate individual desire and collective purpose to later scientific paradigms that understood it as a pathological individual deviation that nevertheless produced cultural progress, ideas of genius provided a rich language for contests over women's citizenship. Feminist narratives of female genius projected desires for a modern public life open to new participants and new kinds of collaboration, even as philosophical and scientific ideas of intelligence and creativity could often disclose troubling and more regressive dimensions. Elucidating how ideas of genius facilitated debates about political agency, gendered identity, the nature of consciousness, intellectual property, race, and national culture, Olwell reveals oppositional ways of imagining women's citizenship, ways that were critical of the conceptual limits of American democracy as usual.Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 304

- Langue:

- Anglais

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780812243246

- Date de parution :

- 02-06-11

- Format:

- Livre relié

- Format numérique:

- Genaaid

- Dimensions :

- 152 mm x 229 mm

- Poids :

- 544 g