- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

42,95 €

+ 85 points

Description

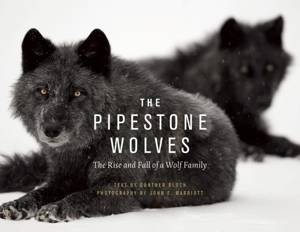

In the winter of 2008-2009, a new wolf family from the Pipestone Valley suddenly appeared in the Bow Valley of Banff National Park, taking up residence alongside the Bow Valley wolf family that had ruled there for over a decade. Within a year, these new wolves had eliminated the Bow Valley wolves and established a dominance that would last for five years in the heart of Canada's most famous national park. As the climactic chapter in a twenty-year observational study of wolves in Banff National Park, internationally respected wolf behavior expert Günther Bloch and widely renowned wildlife photographer John E. Marriott followed the Pipestones through the trials and tribulations of raising their family in one of the world's most heavily visited national parks. Bloch's work involved patient, time-consuming observations day after day for five consecutive years, resulting in matchless ecological and behavioral insights that go beyond the usual information that comes from studying wild wolves using telemetry and radio collaring. Bloch outlines the differences between a wolf pack and a wolf family, he describes A- and B-type personalities in wolves and how this impacted survival rates of the Pipestone pups and yearlings in the Bow Valley. He also details the three societal types of wild wolves, debunking the age-old myth of a pecking order from alphas to omegas, based on what he was able to observe in person with these wild wolves. Throughout the book, Bloch and Marriott describe some of the incredible wolf behavior they were fortunate enough to witness as part of the study. They watched a yearling female called Blizzard play with a mouse in the middle of the road for twenty minutes one frigid winter morning and saw the family playing tug-of-war one afternoon with a pair of men's boxer shorts. The most interesting observation was near the end of the family's dominance when a yearling named Yuma brought food repeatedly to a young pup called Sunshine that had suffered a broken leg after getting hit by a train. Sunshine lived on to become the last surviving member of the family. The book chronicles not only the rise of the Pipestones and how they established and maintained dominance in the valley, but also how an increase in mass tourism in Banff led to a decrease in prey density for the Pipestones, which in turn led to the wolves changing their hunting strategies and expanding their summer range. Bloch explains how the Pipestones faced an inevitable fall from the top as pressure from eager wolf watchers increased exponentially in the park at the same time the Wolves' prey base was shrinking rapidly. Combining these influences with other factors like rail mortality and old age, Bloch and Marriott knew the end was near for the Pipestones. The authors conclude with insights into how wolf and wildlife management in Banff National Park can improve. They outline steps Parks Canada should be taking to deal with the human management problems that are really at the core of the wildlife issues in the park. They also discuss whether we can continue to maintain a balance between ecological integrity and mass tourism in Canada's flagship park and whether it is already too late. Have we passed the point of no return? And will our Banff wolves live forever after in a wildlife ghetto devoid of true wilderness characteristics?

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 192

- Langue:

- Anglais

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9781771601603

- Date de parution :

- 20-09-16

- Format:

- Livre relié

- Format numérique:

- Genaaid

- Dimensions :

- 279 mm x 216 mm

- Poids :

- 1374 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.