- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

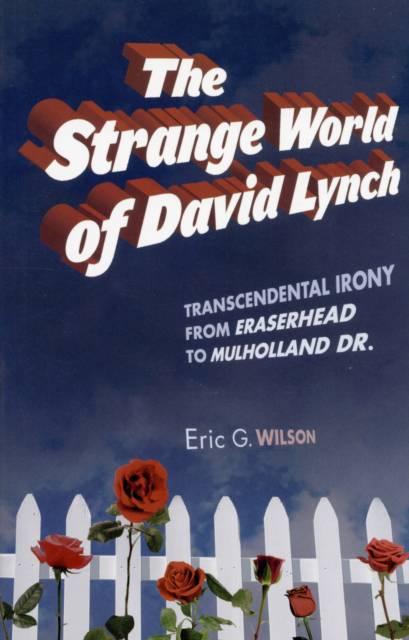

The Strange World of David Lynch

Transcendental Irony from Eraserhead to Mulholland Dr.

Eric G Wilson

Livre broché | Anglais

69,45 €

+ 138 points

Description

Anyone who has sat through the dark and grainy world of Eraserhead knows that David Lynch's fi lms pull us into a strange world where reality turns upside down and sideways. His fi lms are carnivals that allow us to transcend our ordinary lives and to reverse the meanings we live with in our daily lives. Nowhere is this demonstrated better than in the opening scene of Blue Velvet when our worlds are literally turned on their ears.

Lynch endlessly vacillates between Hollywood conventions and avant-garde experimentation, placing viewers in the awkward position of not knowing when the image is serious and when it's in jest, when meaning is lucid or when it's lost. His vexed style in this way places form and content in a perpetually self-consuming dialogue. But what do Lynch's fi lms have to do with religion? Wilson aims to answer that question in his new book, The Strange World of David Lynch.To say that irony (especially of the kind found in Lynch's fi lms) generates religious experience is to suggest religious can be founded on nihilism. Moreover, in claiming Lynch's fi lms are religious, one must assume that extremely violent and lurid sexual films are somehow expressions of energies of peace, tranquility, and love. Wilson illuminates not only Lynch's fi lm but also the study of religion and fi lm by showing that the most profound cinematic experiences of religion have very little to do with traditional belief systems. His book offers fresh ways of connecting the cinematic image to the sacred experience.

Anyone who has sat through the dark and grainy world of Eraserhead knows that David Lynch's fi lms pull us into a strange world where reality turns upside down and sideways. His fi lms are carnivals that allow us to transcend our ordinary lives and to reverse the meanings we live with in our daily lives. Nowhere is this demonstrated better than in the opening scene of Blue Velvet when our worlds are literally turned on their ears. Lynch endlessly vacillates between Hollywood conventions and avant-garde experimentation, placing viewers in the awkward position of not knowing when the image is serious and when it's in jest, when meaning is lucid or when it's lost. His vexed style in this way places form and content in a perpetually self-consuming dialogue. But what do Lynch's fi lms have to do with religion? Wilson aims to answer that question in his new book, The Strange World of David Lynch.

To say that irony (especially of the kind found in Lynch's fi lms) generates religious experience is to suggest religious can be founded on nihilism. Moreover, in claiming Lynch's fi lms are religious, one must assume that extremely violent and lurid sexual films are somehow expressions of energies of peace, tranquility, and love. Wilson illuminates not only Lynch's fi lm but also the study of religion and fi lm by showing that the most profound cinematic experiences of religion have very little to do with traditional belief systems. His book offers fresh ways of connecting the cinematic image to the sacred experience.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 192

- Langue:

- Anglais

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780826428240

- Date de parution :

- 01-06-07

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 136 mm x 220 mm

- Poids :

- 249 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.