- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

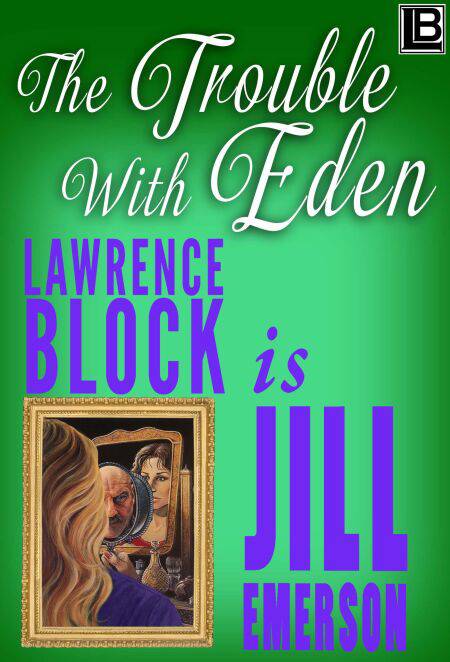

n early 1969, I moved with my wife and daughters to an 18th century farmhouse on twelve rolling acres a mile east of the Delaware River. We kept a variety of animals and grew things in the garden, and this was as I’d expected. But there were two things I did not anticipate. One was that I would have to go away from there, all the way back to New York City, to get any work done. The other was that I’d open an art gallery.

The art gallery was in New Hope, right across the river from Lambertville. New Hope had long had a reputation as an artists’ colony and boasted a little theater and a batch of art galleries, along with bookstores and antique dealers and cute little shops to sell cute little things to tourists, most of whom were neither cute nor little.

I found a store for rent and signed a year’s lease. Nowadays it’s hard to get me to go see a movie or buy a new shirt, but back then I’d embark on the wildest adventure on not much more than a whim.

I knew nothing about business, but that was okay, because the gallery didn’t do any. After a year, my lease was up and I was out of there. It was a learning experience, and what I learned was not to make that particular mistake again.

And I did meet some interesting people, and hear some interesting stories. And, when it came time to write a big trashy commercial novel, I knew right where to set it.

By this time I’d written three erotic novels for Berkley Books as Jill Emerson. Now I don’t know who thought that Jill ought to write a big, juicy, trashy Peyton Place–type of book, but my agent brought the idea to me, and I thought Bucks Country would provide a good setting.

The deal was an attractive one, with a hefty advance. Berkley was a division of Putnam, and the deal was hard/soft; the book would be first a Berkley hardcover, then a paperback.

When we’d first moved to the country and I found I couldn’t get any writing done there, I went into the city and wrote a book in a week. Soon after that Brian Garfield and I took a place together at 235 West End Avenue. We hosted a weekly poker game there, stayed over when one or the other of us had a late night in the city, and got some writing done. I believe Brian wrote most of Kolchak’s Gold there. I wrote a batch of things, too, and one of them was The Trouble with Eden.

Berkley, bestseller hopes notwithstanding, never put any muscle into the book. It didn’t sell many copies.

Reviewers overlooked it completely, with a single curious exception. A reviewer in Esquire launched into a lengthy discussion of a book he’d picked up a week earlier without great expectations. It looked like trash but turned out to be far more gripping and involving than he anticipated. Well-wrought characters, interesting plot developments—really pretty good.

And then suddenly the review hung a U-turn, and its author said that further on the book turned out to be trash after all and, on balance, a big disappointment. I’ll tell you, it was as though the reviewer read half the book, wrote half the review, ate a bad clam, finished the book, and went on to finish the review. I can’t say I minded—it was, as they say at the Oscars, victory enough merely to be nominated—and I can’t say I disagreed with its conclusion. But it was damn strange.

Ah well. It’s probably not a good book, but I have a warm spot for Eden. Like the curate’s egg, I think parts of it are very good.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9781536557787

- Date de parution :

- 26-09-16

- Format:

- Ebook

- Protection digitale:

- /

- Format numérique:

- ePub

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.