- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

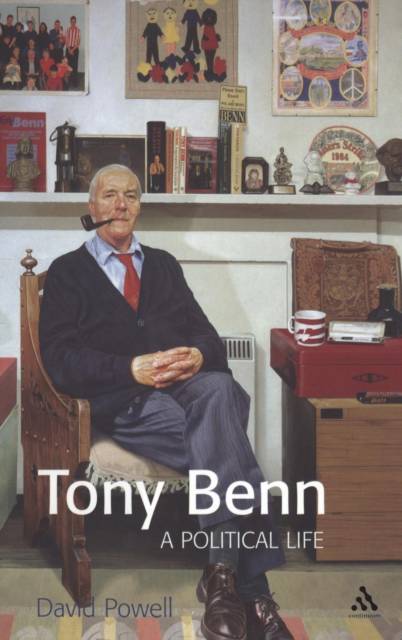

For much of his half-century career in the House of Commons, Tony Benn has been the most loved and loathed man in British politics. He has been idolized by the left, and reviled with equal measure by the Westminster establishment, not least by New Labour. Once tipped to lead the Labour Party, Benn's growing disillusionment with what he regarded as the "democratic deficit" infecting politics, reinforced his resolve to continue playing the role he valued most, as "a good House of Commons Man".David Powell's fascinating new biography traces Tony Benn's extraordinary fifty year political career from the day he first entered the House in 1950. He argues that Benn's commitment to the House of Commons was fortified by his experiences during the thirty months when he fought to renounce his peerage and remain an MP; then during the twelve years he spent in government, and finally during the two decades he spent on the back benches, having been defeated in the bruising campaign for the Deputy Leadership of the Labour Party. Each was to provide him with an insight into the workings of power and cumulatively they were to convince him of the charade that passed for democracy not only in Westminster and in the Labour Party, but in the European Union and in the wider in the global context, with democratic ideals subordinated to the political and economic power of the United States. Benn has always a controversial figure. He was widely caricatured as "Bogey Benn" by the Tories during the 1970s and was more recently anathematised by Tony Blair as the man who "almost knocked the Labour party over the edge of the cliff into extinction". Nonetheless many of the policies he championed, and for which he was widely belittled, have since entered the statute books. Indeed, if history is a chronicle of ironies, there can have been little more ironic than when, following Benn's valedictory speech in the Commons in 2001, a Tory backbencher commended him to fellow MPs as Britain's "greatest living Parliamentarian".

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 208

- Langue:

- Anglais

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780826456991

- Date de parution :

- 12-11-01

- Format:

- Livre relié

- Format numérique:

- Genaaid

- Dimensions :

- 155 mm x 234 mm

- Poids :

- 453 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.