- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

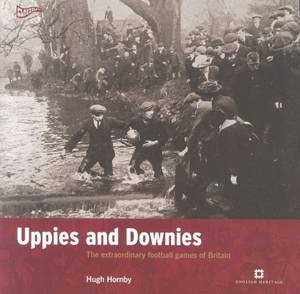

Association football, aka 'soccer', is the world's most popular sport. As is known, its rules were drawn up in England between the 1840s and 1860s, largely at the behest of ex public school and university players. Rugby, another version of football honed between the 1820s and 1870s, split from the Association clubs in the 1870s, and subsequently split itself into Rugby Union and Rugby League in the 1890s. Meanwhile, different versions of football developed in the US and Australia. Ireland has its own version, called Gaelic Football. Amid all these developments, and in stark contrast to the riches and glamour of the modern Premiership and the World Cup, around 25 traditional football games continue to be played in various parts of Britain. Their origins may be traced back to at least the 12th century, when rival group of apprentices would play an early form of mob football on holy days. Despite the geographical spread (from Cornwall to the Shetlands) these folk games share several common strands. There have been previous studies of the Kirkwall Ba' Game and of the Ashbourne Shrove Tuesday game, but Uppies and Downies will be the first book to analyse the games as part of a collective tradition. Uppies and Downies - The title of the book refers to the most common name given to teams playing in these games. Most are played in the streets and fields of small towns and villages. Those living in the upper, or most northerly part of the district, play for the Uppies; those in the lower, or most southerly part, play for the Downies (or Doonies in Scotland). Unlike soccer or rugby, there are no designated pitches or boundaries. The 'goals' are specified locations (a tree, a bridge, a wall, a gate), often two or three miles apart. There is no distinction between spectators and players. Players drop out for a period to watch. Spectators may join in for short periods. Games can take less than an hour, or continue for several hours, often ending in darkness. Once a goal is scored, the game ends.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 180

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9781905624645

- Date de parution :

- 28-02-08

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 206 mm x 208 mm

- Poids :

- 612 g