- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

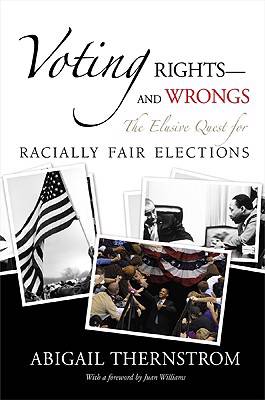

Voting Rights--And Wrongs

The Elusive Quest for Racially Fair Elections

Abigail Thernstrom

Livre broché | Anglais

27,95 €

+ 55 points

Format

Description

The 1965 Voting Rights Act is the crown jewel of American civil rights legislation. Its passage marked the death knell of the Jim Crow South. But that was the beginning, not the end, of an important debate on race and representation in American democracy. When is the distribution of political power racially fair? Who counts as a representative of black and Hispanic interests? How we answer such questions shapes our politics and public policy in profound but often unrecognized ways. The act's original aim was simple: Give African Americans the same political opportunity enjoyed by other citizens--the chance to vote, form political coalitions, and elect the candidates of their choice. But in the racist South, it soon became clear that access to the ballot would not, by itself, provide the political opportunity the statute promised. Most southern whites were unwilling to vote for black candidates, and southern states were ready to alter electoral systems to maintain white supremacy. In this provocative book, Abigail Thernstrom argues that southern resistance to black political power began a process by which the act was radically revised both for good and ill. Congress, the courts, and the Justice Department altered the statute to ensure the election of blacks and Hispanics to legislative bodies ranging from school boards and county councils to the U.S. Congress. Proportional racial representation--equality of results rather than mere equal opportunity--became the revised aim of the act. Blacks came to be treated as politically different--entitled to inequality in the form of a unique political privilege. Majority-minority districts that reserved seats for blacks and Hispanics succeeded in integrating southern politics. By now, however, those districts may perversely limit the potential power of black officeholders. "Max-black" districts typically elect candidates to the left of most voters; those officeholders rarely win in majority-white settings. Such race-conscious districting discourages the development o

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 316

- Langue:

- Anglais

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780844742724

- Date de parution :

- 01-07-09

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 150 mm x 226 mm

- Poids :

- 498 g