- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

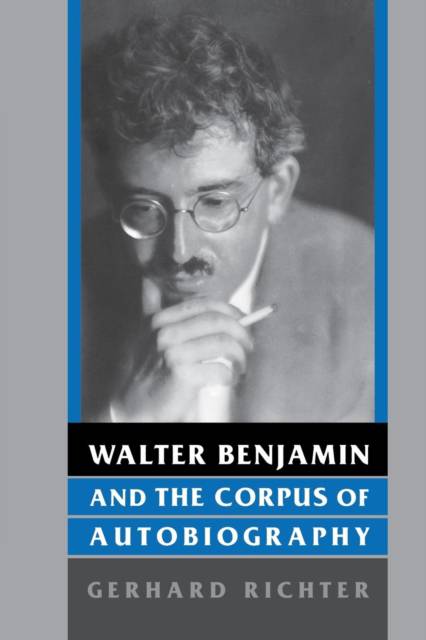

Although Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) is considered one of the most significant writers and theorists in twentieth-century Western culture, his enigmatic sense of the political has eluded definition. His later work in particular stages a perpetual but little understood confrontation with German fascism.

Gerhard Richter shows that Benjamin's engagement with the political cannot be understood in terms of unified concepts and fully deducible theses that can be easily verified or refuted. Rather than explaining his sense of the political, Benjamin enacts it in the movement of his language. Richter traces Benjamin's radical notions of the political through a series of corporeal figures in his often neglected autobiographical writings--the Moscow Diary, the Berlin Chronicle, and the Berlin Childhood around 1900. Each text subtly mobilizes a different trope of anatomy: the body, the ear, and the eye. Richter places these figures into a wide network of references from Benjamin's corpus demonstrating that Benjamin's innovative acts of self-portraiture are inseparable from his analyses of the physiognomy of Weimar culture and German fascism. Benjamin's preoccupation with the body becomes visible as a political struggle that illuminates the relations among the self, history, reading, and language. Benjamin's autobiographies, as Richter shows, negate fascism and its ideology of stable meaning with each turn away from an essential corporeal self.

Readers interested in modem German literature and culture, literary and cultural theory, comparative literature, Weimar culture, and fascism will welcome this book.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 312

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780814330838

- Date de parution :

- 01-04-02

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 152 mm x 229 mm

- Poids :

- 417 g