En raison d'une grêve chez bpost, votre commande pourrait être retardée. Vous avez besoin d’un livre rapidement ? Nos magasins vous accueillent à bras ouverts !

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

En raison de la grêve chez bpost, votre commande pourrait être retardée. Vous avez besoin d’un livre rapidement ? Nos magasins vous accueillent à bras ouverts !

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

20,95 €

+ 41 points

Description

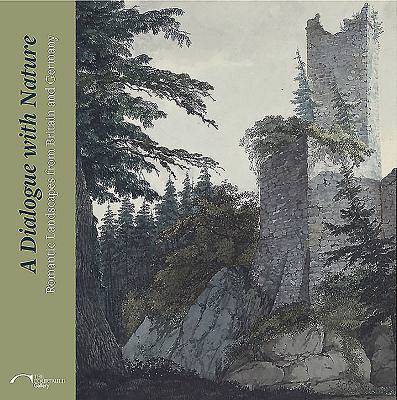

"The artist should not only paint what he sees before him," claimed Caspar David Friedrich, "but also what he sees in himself". He should have "a dialogue with Nature". Friedrich's words encapsulate two central elements of the Romantic conception of landscape: close observation of the natural world and the importance of the imagination. Exploring aspects of Romantic landscape drawing in Britain and Germany from its origins in the 1760s to its final flowering in the 1840s, this exhibition catalogue considers 26 major drawings, watercolors and oil sketches from The Courtauld Gallery, London, and the Morgan Library and Museum, New York, by artists such as J.M.W. Turner, Samuel Palmer, Caspar David Friedrich and Karl Friedrich Lessing. It draws upon the complementary strengths of both collections: the Morgan's exceptional group of German drawings and The Courtauld's wide-ranging holdings of British works. A Dialogue with Nature offers the opportunity to consider points of commonality as well as divergence between two distinctive schools. The legacy of Claude Lorrain's idealizing vision is visible in Jakob Hackert's magisterial view of ruins at Tivoli, near Rome, as well as in a more intimate but purely imaginary rural scene by Thomas Gainsborough, while cloud and tree studies by John Constable and Johann Georg von Dillis demonstrate the importance of drawing from life and the observation of natural phenomena. The important visionary strand of Romanticism is brought to the fore in a group of works centered on Friedrich's evocative Moonlit Landscape and Samuel Palmer's Oak Tree and Beech, Lullingstone Park. Both are exemplary of their creators' intensely spiritual vision of nature as well as their strikingly different techniques, Friedrich's painstakingly fine detail contrasting with the dynamic freedom of Palmer's penwork. The most expansive and painterly works include Turner's St Goarshausen and Katz Castle, the luminous simplicity of Francis Towne's watercolor view of a wooded valley in Wales, and Friedrich's subtle wash drawing of a coastal meadow on the remote Baltic island of Rügen. Three small-scale drawings reveal a more introspective and intimate facet of the Romantic approach to landscape: Theodor Rehbenitz's fantastical medievalising scene, Palmer's meditative Haunted Stream, and lastly, Turner's Cologne, made as an illustration for The Life and Works of Lord Byron (1833).

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 84

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9781907372667

- Date de parution :

- 20-05-14

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 203 mm x 208 mm

- Poids :

- 294 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.