- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

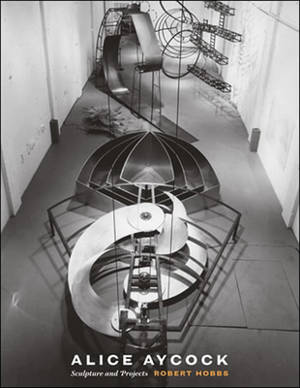

Alice Aycock's large, semi-architectural works deal with the interaction of structure, site, materials, and the psychophysical responses of the viewer. Offered meaningful but contradictory clues by both her images and her texts, viewers attempt to discover not only what the work of art conveys but how it communicates its contents, in investigations that parallel the artist's own. In Alice Aycock: Sculpture and Projects, Robert Hobbs examines the development of Aycock's work over twenty years and her negotiation--along with other artists who came of age in the early 1970s--of the transition from modernism to postmodernism. "The problem," wrote Aycock in 1977, "seems to be how to connect without connecting." Hobbs describes Aycock's strategies for doing just this: for creating a work with disparate image and texts that offer a new perspective on reality. Influenced by the "specific objects" of minimalism's hybrid forms and by conceptualism's emphasis on language, Aycock relies on paradigms, cybernetics, phenomenology, physics, post-structuralism, psychoanalysis, information overload, outdated scientific thinking, and computer programming to create a "complex" that is architectural and sculptural as well as mental and emotional. Schizophrenia and other mental conditions, sometimes considered metaphors for the disconnections of postmodern existence, are specific sources of inspiration in Aycock's work. By exploring the physical and existential positions of isolation, estrangement, disorientation, entrapment and fear, her three-dimensional constructions not only posit alternative states of mind, they suppose possible narratives and suggest multiple truths and lies. Aycock's work invites the viewer to experience sculpture with the entire body and a fully mind. Her sculpture has had a transformative effect on the contemporary art experience.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 400

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780262083393

- Date de parution :

- 09-09-05

- Format:

- Livre relié

- Format numérique:

- Genaaid

- Dimensions :

- 226 mm x 287 mm

- Poids :

- 2349 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.