- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

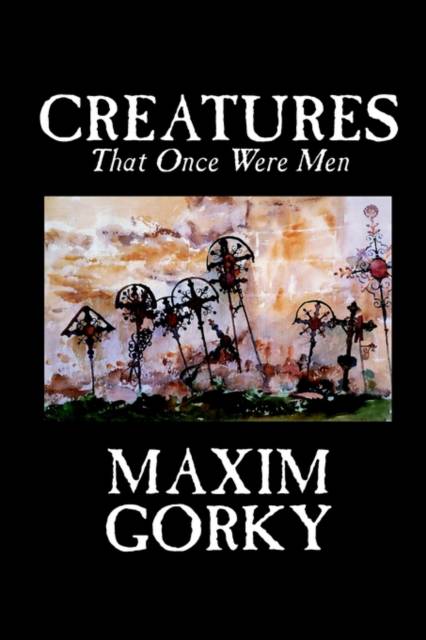

In the very act of describing a kind of a fall from humanity, Gorky expresses a sense of the strangeness and essential value of the human being which is far too commonly absent altogether from such complex civilizations as our own. To no Westerner, I am afraid, would it occur, when asked what he was, to say, "A man." He would be a plasterer who had walked from Reading, or an iron-puddler who had been thrown out of work in Lancashire, or a University man who would be really most grateful for the loan of five shillings, or the son of a lieutenant-general living in Brighton, who would not have made such an application if he had not known that he was talking to another gentleman. With us it is not a question of men being of various kinds; with us the kinds are almost different animals. But in spite of all Gorky's superficial skepticism and brutality, it is to him the fall from humanity, or the apparent fall from humanity, which is not merely great and lamentable, but essential and even mystical. The line between man and the beasts is one of the transcendental essentials of every religion; and it is, like most of the transcendental things of religion, identical with the main sentiments of the man of common sense. We feel this gulf when theologies say that it cannot be crossed. But we feel it quite as much (and that with a primal shudder) when philosophers or fanciful writers suggest that it might be crossed. And if any man wishes to discover whether or no he has really learned to regard the line between man and brute as merely relative and evolutionary, let him say again to himself those frightful words, "Creatures That Once Were Men." -- G. K. Chesterton

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 228

- Langue:

- Anglais

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9781592244607

- Date de parution :

- 01-09-03

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 152 mm x 229 mm

- Poids :

- 340 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.