- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

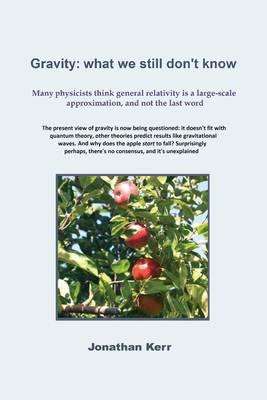

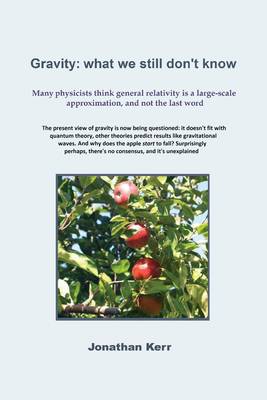

Recently, well-known physicists like Raphael Bousso and Sabine Hossenfelder have broken the taboo, and come out and said what many have thought for longer: that general relativity is a large-scale approximation. It works very well in its own domain, as Newton's theory did. But it doesn't fit with quantum theory, as small-scale physics is outside its domain.

Raphael Bousso: 'But as a matter of principle, the theory is wrong. The seed is there. General relativity cannot be the final word; it can only be an approximation [...] '

Sabine Hossenfelder: 'Most physicists, myself included, think general relativity is only an approximation to a better theory'. And elsewhere: 'But we already know that it cannot ultimately be the correct theory for space and time. It is an approximation that works in many circumstances, but fails in others.'So although special relativity is above suspicion, nowadays the gravity theory isn't. And gravitational waves are predicted by a list of other theories, as well as general relativity. In this book, Jonathan Kerr looks at the real issues about gravity, the recent interest in new gravity theories, and the efforts to replace ideas that aren't working well with the rest of the landscape. Quantum theory, by contrast, has connected well with other physics in many places, and the standard model is based on it.

Later in the book, the author explains his own solution, which comes out of the same background theory that two of the world's top physicists, Carlo Rovelli and Neil Turok, became interested in after documentary maker Nigel Lesmoir-Gordon sent them his paper. They discussed the quantum mechanics part of the theory with Jonathan Kerr in the online documentary The Interactions Avenue. There was a Sunday Telegraph article, Quantum mechanics' greatest puzzle 'solved' in a Surrey cottage.

The theory is about the Planck scale, the smallest scale we know of, which is still uncharted: there's no consensus about what the world is like there, but it seems clear that it's vital to physics, and that much of what we find at larger scales arises from there. Because of string theory, many physicists think Planck scale geometry is highly complicated. But Kerr put in simple but lateral conceptual changes, treating matter as 'spinning light' at that scale - it has led to some surprising predictions.

Planck scale gravity says that if light and matter are released at right angles in a gravitational field (light to travel horizontally, matter to fall vertically), both will reach the surface of the mass at exactly the same moment, if they both do. Standard theory agrees to eight decimal places, but only PSG has a full explanation. The rule was found via PSG in 2021.

In 1971, Apollo 15 astronaut David Scott dropped a hammer and a falcon's feather on the moon. There was no need to confirm Galileo's discovery, or his experiment centuries earlier (which according to legend involved dropping weights from the leaning tower of Pisa). But with no air resistance and less gravity, it demonstrated the principle well. As expected, they fell slowly side by side, and hit the ground at the same time. Now it has been shown that light and matter do the same thing.

It's far from obvious why they hit the ground at the same time. The rule may have been known by a few, but not many, as no-one was looking for it. But the new geometry led right to it, and the theory has a simple, unexpected explanation - for this and many other phenomena.

As with Kerr's first book, The Unsolved Puzzle, this book is for both physicists and popular science readers. It brings a whole new take on one area of physics - and gravity is an area that many know well enough to understand the old questions, and the simple, surprising new ways to answer them.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 230

- Langue:

- Anglais

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780956422231

- Date de parution :

- 04-02-23

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 156 mm x 234 mm

- Poids :

- 326 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.