- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

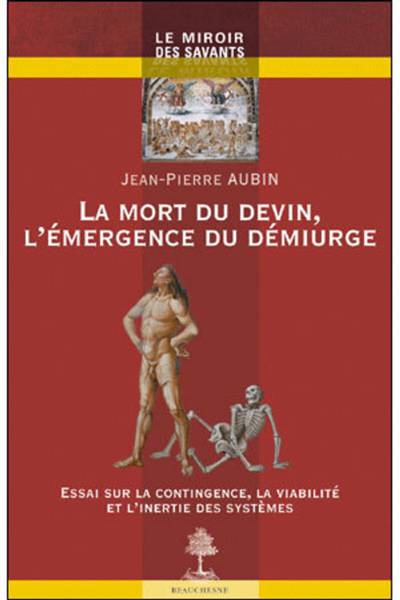

La mort du devin, l'émergence du démiurge

essai sur la contingence, la viabilité et l'inertie des systèmes

Jean-Pierre AubinDescription

Le miroir des savants

La mort du devin, l'émergence du démiurge

Essai sur la contingence, la viabilité et l'inertie des systèmes

Depuis les premiers mythes de la création en passant par Fermat, un consensus s'est formé chez la plupart des physiciens et des mathématiciens pour accepter l'hypothèse que ce monde est le meilleur des mondes physiques et prévisibles. Peu mettent en doute que nos variables - celles qu'observe noire cerveau - ne sauraient évoluer sans pilote. Jean-Pierre Aubin l'appelle le Devin : omniscient, il connaît l'avenir, le bien et le mal, il est capable de rechercher et de trouver la meilleure parmi toutes les évolutions possibles au long du temps.

Mais il est des variables dont on peut se demander si elles n'échappent pas au pouvoir du Devin - les gènes, les codes culturels, les prix, les idées, d'autres encore. Jean-Pierre Aubin classe ce type de variable sous le nom de régulons et désigne le responsable de leur évolution : c'est le Démiurge. Il est myope, paresseux, mais explorateur, conservateur, ma s opportuniste. Confronté à la nécessité d'adapter à chaque instant ses variables à un environnement qui lui est imposé, le Démiurge régule leur possible évolution viable. Le Devin prend des décisions optimales. Le Démiurge, lui, les prend à temps pour modifier les régulons lorsque la viabilité est en jeu.

Le comportement du Devin motive depuis des siècles d'innombrables travaux mathématiques. Ce n'est que depuis trente ans que des mathématiciens élaborent des métaphores du comportement du Démiurge à l'aide de nouveaux concepts et outils mathématiques venant s'ajouter à ceux conçus pour rendre compte du monde inerte. Les décrire est l'objet de la seconde partie de cet ouvrage.

Auparavant, l'auteur mené son enquête sur l'évolution dans les divers champs de la biologie, de la sociologie, de l'économie, des sciences cognitives, depuis la phylogenèse jusqu'à la finance. Pour le plaisir de l'esprit et de la découverte, Jean-Pierre Aubin dévore le monde vivant en ogre mathématicien.

The Death of the Seer, the rise of the Demiurge

Essay on contingency, viability, and inertia of systems

¤ Contingency of evolutions due to the redundancy of the regulons governing them ;

¤ viability of their trajectories constrained to be confined in an environment ;

¤ inertia principle stating that regulons are modified only during periods of crisis, when their continued viability is at stake ; are the three main themes of this essay.

The book deals with a series of mathematical metaphors to explain how a Demiurge, shortsighted, lazy but explorer, conservative but opportunistic, regulates evolutions, rather than a clairvoyant and omniscient Seer, acting with a sure and visible hand on control inputs to optimize intertemporal criteria only known to him. The Demiurge regulates viable evolutions, whatever the disturbances that Tyche, the goddess of luck or fortune, distributes, without any statistical regularity regarding her good or ill-will.

The environment is symbolized by a picture representing the trajectory of a viable evolution governed by three constant regulons outside the crisis periods. Whenever the evolution is about to leave the environment, the regulon must evolve during a "viability crisis" until the next moment when the regulon remains constant while driving a viable evolution, and so on.

Instead of seeking optimal decisions, as the seer, the demiurge takes timely decisions, whenever the evolution is about to leave the environment, acting through regulons during a period of « viability crisis », which comes to an end with a new regulon taking over control of the evolution, until the next viability crisis.

The first part searches for these features in several fields of the life sciences, from biology to cognitive science, from phylogeny to the social sciences. The second part describes in vernacular language mathematical metapors of Darwinian evolution, based on chance and subject to necessity. They offer the reader mathematical keys to understanding how viable evolutions are regulated by the demiurge, consistent with paths mapped out by Lamarck and Darwin, and at odds with ideas of Fermat explaining how the seen pilots optimal evolutions (the « best one », according to Leibniz) in the physical world.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 896

- Langue:

- Français

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9782701015040

- Date de parution :

- 05-11-10

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Dimensions :

- 160 mm x 240 mm

- Poids :

- 1390 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.