- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

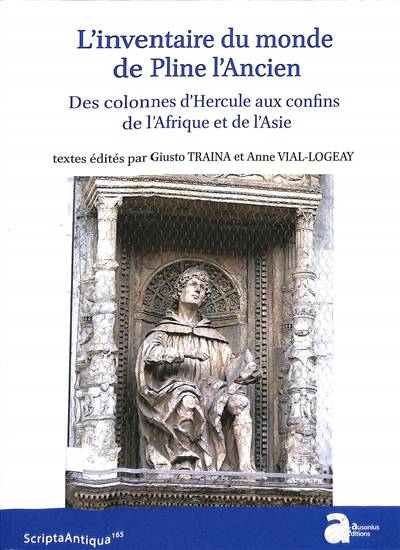

L'inventaire du monde de Pline l'Ancien

des colonnes d'Hercule aux confins de l'Afrique et de l'Asie

Traina GiustoDescription

L'inventaire du monde de Pline l'Ancien

Des colonnes d'Hercule aux confins de l'Afrique et de l'Asie

Selon l'expression créée par le latiniste italien Gian Biagio Conte et popularisée dans la littérature scientifique par l'historien français Claude Nicolet, on peut considérer l'Histoire naturelle de Pline l'Ancien (C. Plinius Secundus, 23-79 p.C.) comme un véritable "inventaire du monde" romain autour du Ier s. p.C. Cette appréciation ne se limite pas aux livres 3-6, consacrés à la géographie. En fait, les 37 livres de cette œuvre qui transmit au Modernes le savoir des Anciens peuvent être utilisés entre autres dans une perspective à la fois géographique et ethnographique. Car Pline, dans son travail de compilation savante et avisée, conduit avec une discipline de fer (son neveu et fils adoptif Pline le Jeune le raconta dans une célèbre épître : « il avait un génie vigoureux, une ardeur extraordinaire, une très grande puissance de veille. Il commençait à travailler à la lumière (...) pour s'assurer non d'heureux auspices, mais le temps d'étudier, et cela une fois la nuit bien tombée », Lettres, III, 5), ne s'est pas limité à rassembler des informations tirées des auteurs romains et "étrangers", pour la plupart des Grecs, mais a régulièrement mis en valeur les premiers, dans l'ambition de s'affranchir du poids des autorités grecques et de présenter le monde vu par un Romain.

C'est sur le double aspect d'héritage culturel et de recension, deux dimensions généralement associées au terme d'inventaire, que nous avons voulu insister pour donner les lignes directrices de ce recueil d'articles, issu d'un séminaire tenu à Paris-Sorbonne, au premier semestre de l'année universitaire 2016/2017. De l'Afrique du nord au Caucase et à l'Iran, en passant par la Grèce, l'Asie mineure et l'Égypte (sans négliger, bien entendu, la ville de Rome ni l'Italie), nous proposons une série de contributions dans le but d'apporter de nouveaux matériaux à l'appui de l'interprétation d'un texte fondamental pour la compréhension du Principat romain.

To define Pliny the Elder's Natural History, the Italian Latinist Gian Biagio Conte coined a fitting expression: « L'inventario del mondo » (the Inventory of the World), subsequently taken up by the French historian Claude Nicolet in his book L'inventaire du monde. Pliny's work may actually be considered as taking stock of the ancient world and of its cultural heritage around 70 CE. This holds not only for the geographical gazetteer forming books 3-6, but also for Pliny's whole work, which can be studied from a geographical and an ethnographical perspective.

In writing his learned and thoughtful compilation, Pliny followed an iron discipline, as we know from a letter by his nephew and adoptive son Pliny the Younger: « He combined a penetrating intellect with amazing powers of concentration and the capacity to manage with the minimum of sleep. From the feast of Vulcan onwards he began to work by lamplight, not with any idea of making a propitious start but to give himself more time for study, and would rise half-way through the night; in winter it would often be at midnight or an hour later, and two at the latest » (Letters, III, 5, 8).

But Pliny did not limit himself to gathering a huge amount of information from Roman and « foreign » (mostly Greek) authors. He also processed these materials to present a Roman world that surpassed the Hellenistic tradition.

The papers of this collection were presented at a seminar held in Paris in 2016. They encompass a large geographical scale from North Africa to the Caucasus and Iran, via Greece, Asia Minor, and Egypt (without neglecting the city of Rome and Italy), proposing new contributions to the understanding of Pliny's Natural History and, of course, of the Roman world in the first century of our era.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 187

- Langue:

- Français

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9782356135247

- Date de parution :

- 09-09-22

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Dimensions :

- 170 mm x 240 mm

- Poids :

- 369 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.