- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

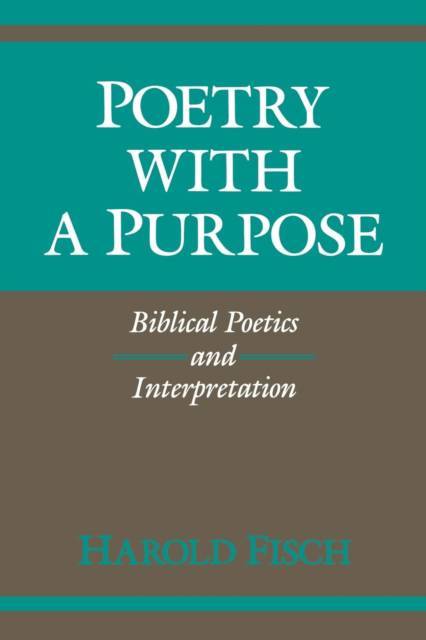

Do Old Testament poetry and narrative, wisdom-writing and prophecy work on us in the same way as do nonbiblical literary texts? Competent readers over the centuries have arrived at conflicting answers to this question. Some (from Longinus on) have maintained that biblical books offer examples of supreme literary art; others have passionately rejected this approach, insisting that beauty and pleasure are not the Bible's business.

Poetry with a Purpose argues that, paradoxically, both views are right. Biblical poetics is marked by an unusual tension between aesthetic and nonaesthetic (even anti-aesthetic) modes of discourse. To understand this dialectic is to understand something quite fundamental about biblical texts and, more particularly, about the nature of the contract that governs their reading. The text summons the reader to respond to a familiar form but at the same instant undermines that response, deconstructs that form. The book of Ester, for example, displays the conventions of the Persian epic tradition, but its style is subtly challenged by the text itself. Similarly, the book of Job might seem to conform to the classical concept of tragedy but ultimately presents a uniquely biblical version of the form. While the prophets use the language of myth, they will often explode or "demythologize" their own language, affirming purposed at variance with the world of myth.

Harold Fisch applies his remarkably fruitful thesis to a number of biblical texts and modes, among them biblical pastoral, the Song of Songs, Psalms, Hosea, and Ecclesiastes. Equally at home in biblical studies and in general literature and theory, the author has produced a highly original work of unusual range and scholarship.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 205

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780253205643

- Date de parution :

- 22-02-90

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 152 mm x 229 mm

- Poids :

- 326 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.