En raison d'une grêve chez bpost, votre commande pourrait être retardée. Vous avez besoin d’un livre rapidement ? Nos magasins vous accueillent à bras ouverts !

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

En raison de la grêve chez bpost, votre commande pourrait être retardée. Vous avez besoin d’un livre rapidement ? Nos magasins vous accueillent à bras ouverts !

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

59,45 €

+ 118 points

Description

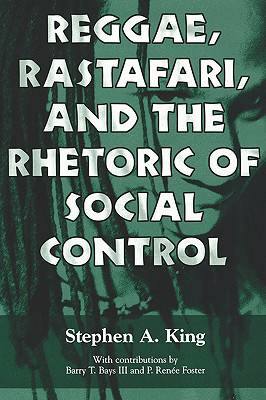

Who changed Bob Marley's famous peace-and-love anthem into "Come to Jamaica and feel all right?" When did the Rastafarian fighting white colonial power become the smiling Rastaman spreading beach towels for American tourists? Drawing on research in social movement theory and protest music, Reggae, Rastafari, and the Rhetoric of Social Control traces the history and rise of reggae and the story of how an island nation commandeered the music to fashion an image and entice tourists. Visitors to Jamaica are often unaware that reggae was a revolutionary music rooted in the suffering of Jamaica's poor. Rastafarians were once a target of police harassment and public condemnation. Now the music is a marketing tool, and the Rastafarians are no longer a "violent counterculture" but an important symbol of Jamaica's new cultural heritage. This book attempts to explain how the Jamaican establishment's strategies of social control influenced the evolutionary direction of both the music and the Rastafarian movement. From 1959 to 1971, Jamaica's popular music became identified with the Rastafarians, a social movement that gave voice to the country's poor black communities. In response to this challenge, the Jamaican government banned politically controversial reggae songs from the airwaves and jailed or deported Rastafarian leaders. Yet when reggae became internationally popular in the 1970s, divisions among Rastafarians grew wider, spawning a number of pseudo-Rastafarians who embraced only the external symbolism of this worldwide religion. Exploiting this opportunity, Jamaica's new Prime Minister, Michael Manley, brought Rastafarian political imagery and themes into the mainstream. Eventually, reggae and Rastafari evolved into Jamaica's chief cultural commodities and tourist attractions.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 200

- Langue:

- Anglais

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9781604730036

- Date de parution :

- 30-11-07

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 152 mm x 229 mm

- Poids :

- 299 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.