En raison d'une grêve chez bpost, votre commande pourrait être retardée. Vous avez besoin d’un livre rapidement ? Nos magasins vous accueillent à bras ouverts !

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

En raison de la grêve chez bpost, votre commande pourrait être retardée. Vous avez besoin d’un livre rapidement ? Nos magasins vous accueillent à bras ouverts !

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

22,45 €

+ 44 points

Format

Description

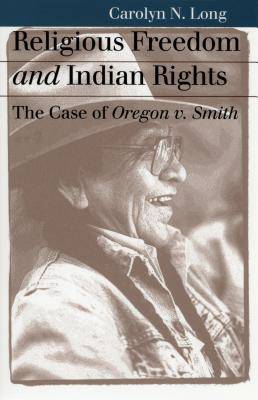

The Supreme Court's controversial decision in Oregon v. Smith sharply departed from previous expansive readings of the First Amendment's religious freedom clause and ignited a firestorm of protest from legal scholars, religious groups, legislators, and Native Americans. Carolyn Long provides the first book-length analysis of Smith and shows why it continues to resonate so deeply in the American psyche. In 1983, Klamath Indian Alfred Smith and his co-worker Galen Black were fired as counselors from a drug rehabilitation agency for using peyote, a controlled substance under Oregon law, in a religious ceremony of the Native American Church. Both were subsequently denied unemployment benefits, which the State of Oregon claimed was permissible under its police powers and necessary in its effort to eradicate drug abuse. But Smith and Black argued that the denial of unemployment benefits constituted an infringement of their religious freedom and took their cases to court. Long traces the tortuous path that Smith followed as it went from state courts to the Supreme Court and then back again for a second round of hearings. A major event in Native American history, the case attracted widespread support for the Indian cause from a diverse array of religious groups eager to protect their own religious freedom. It also led to an intense tug-of-war between the Court and Congress, which fought back with amendments to the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (to protect the religious use of peyote) and the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993, which protected religious freedom for all Americans. The Court subsequently ruled the latter act unconstitutional in Boerne v. Flores (1997). Long provides a lucid and balanced view of the competing sides in Smith. Drawing on interviews with Smith and his family, as well as with lawyers, judges, and congressional and interest group representatives involved in this struggle between Congress and Court, she takes the reader from the rituals of a peyote religious ceremony to the halls of government to reveal the conflicting interests that emerged in this key First Amendment case. She also clarifies how the Court reversed longstanding precedent by replacing the balancing test of "compelling state interest" and "least restrictive means" with a new "reasonable basis" argument that theoretically could be used to curtail religious practices well beyond those of the Native American church. Ultimately, the Supreme Court ruled that the First Amendment protection of religious freedom applies only to laws that specifically target religious behavior and that an individual's religious beliefs do not excuse one from complying with statutes that indirectly infringe on their religious rights. Engagingly written, Long's study highlights the resultant struggles, but without ever losing sight of the rich human dimensions of the story.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 336

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780700610648

- Date de parution :

- 16-01-01

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 141 mm x 217 mm

- Poids :

- 430 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.