En raison d'une grêve chez bpost, votre commande pourrait être retardée. Vous avez besoin d’un livre rapidement ? Nos magasins vous accueillent à bras ouverts !

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

En raison de la grêve chez bpost, votre commande pourrait être retardée. Vous avez besoin d’un livre rapidement ? Nos magasins vous accueillent à bras ouverts !

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

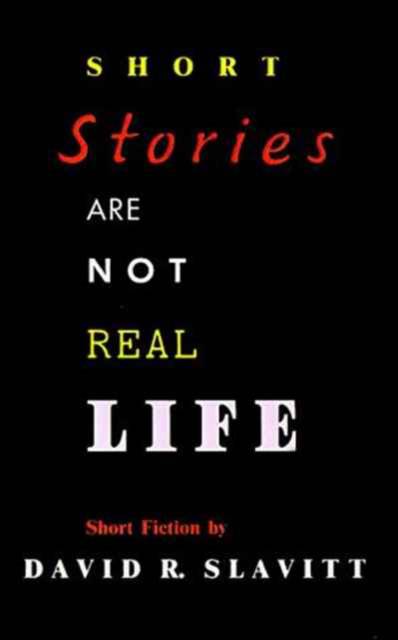

In these fourteen beautifully crafted stories David R. Slavitt shows his mastery of the form. Elegant, spare, sometimes funny, sometimes elegiac--this collection reflects a writer in admirable control of his craft.

The title story (complete with footnotes á la The Norton Anthology of Short Fiction) braids together the tidy conventions of fiction and the brutal reality of New York as a writing teacher ponders s student's sexually explicit story that may--or may not--be autobiographical. In "The Impostor" a writer's brother exploits the legerdemain of fiction in a series of ever-bolder impersonations. Several of the stories are presented by emotionally wounded narrators, disillusioned men looking for a hint of grace in a world where expectations are frequently doomed to disappointment. In such a world only one thing is certain we will hurt--and be hurt by--the ones we love. And in the vacuum left when traditions that might have been redemptive have lost their meaning, "punishment gets to be a habit, a way of life, or at least something to hold onto." The stories pivot on nuance, on the half-realized insight, on "some perfectly innocent and insignificant insight, on "some perfectly innocent and insignificant gesture that turns round and grows into a medium-to-large awkwardness." We find what the divorced father futilely awaiting his daughter's visit in "Hurricane Charlie" calls "dabblers in distress" lonely, decent people trying to discover where love--and life--went. In "Simple Justice" a man striving for some definitive family memory compares the process to archaeology: "The shards that remain are pathetically small and almost grudging." Thus through the faltering memory of an elderly cousin in "conflations" a man becomes a kind of incarnation of his own father and for a moment finds himself at the "vanishing point" where a lost past meets an unknowable future; in "The long Island Train" a simple anecdote becomes a metaphor for the opacity of the most apparently transparent human intentions. Yet it is often these shard of tradition and memory that seem to hold our only promise of transcendence. The protagonist of "Grandfather," for example, through his reluctant participation in his grandson's bris, finds a moment of reconciliation with a past that has broken loose of its moorings. Even the most experimental of these pieces--"Instructions," a list of admonitions ranging from the quotidian to the cosmic--shows a deep humanity and a maturity of vision that steers adeptly between humor and despair. These stories will linger in the reader's memory long after the book is closed.Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 184

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780807124727

- Date de parution :

- 01-03-99

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 140 mm x 216 mm

- Poids :

- 240 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.