- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

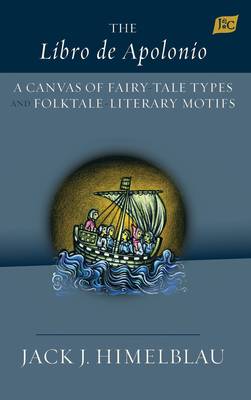

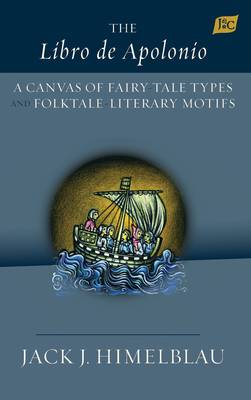

The Libro de Apolonio is an anonymous medieval poetic narrative written in cuaderna vía, a monorhymed quatrain in alexandrine lines. The Spanish novel is a translation and variation of the anonymous late fifth or early sixth-century romance Historia Apollonii Regis Tyri, a Latin diegesis that is mainly written in prose. The thirteenth-century text of the Apolonio is lost. The extant Castilian version is a late fourteenth-century copy (ca. 1390) of the Spanish novel redacted in ca. 1260. The Libro de Apolonio is housed in Spain in the library of El Escorial (codex III-K-4) and forms part of a collection that includes two other texts: the Vida de Madona Santa Maria Egipciaqua and the Libro dels Reyes doriente.

The Libro de Apolonio is an engaging novel whose aesthetic appeal stems from its structured assemblage of fairy-tale types and folktale-literary topoi. With respect to fairy-tale types/folk motifs, this study not only assesses the folktale topoi proffered by scholars of Spanish medieval and Renaissance literatures but also provides additional fairy-tale types/folk motifs. These folk contributions significantly link the Libro de Apolonio (and the Historia Apollonii Regis Tyri, as well) to the timeless realm of folktales.

With respect to the literary motifs, scholars have mainly related the Libro de Apolonio (and the Historia Apollonii Regis Tyri, as well) to classical Greek and Latin literatures as well as to the ancient Greek novels written between the first century CE and late fourth century. However, this study reveals that sources of numerous literary motifs in the Libro de Apolonio (and in the Historia Apollonii Regis Tyri, as well) are variations of topoi that appear in ancient Egyptian and Akkadian literary works that date to 2000 BCE.

Hence, it is reasonable to assume that the oral renditions of the fictive content of the above Mesopotamian and North African texts must date to a time far more remote than that of the Epic of Gilgamesh (ca. 2000 BCE). The question, then, arises: When did the modern human beings become oral narrators of anamneses? This study proposes that, barring grave neurological deficiencies, such as atrophy of the hippocampus, the modern human beings were physiologically born oral storytellers of past events by (if not, before) 300,000 BCE.

Series Estudios de literatura medieval John E. Keller, #15

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 138

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

- Tome:

- n° 15

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9781588713643

- Date de parution :

- 08-12-20

- Format:

- Livre relié

- Format numérique:

- Genaaid

- Dimensions :

- 152 mm x 229 mm

- Poids :

- 353 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.