- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

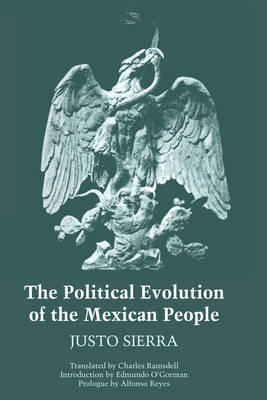

Are the Mexican people the children of Moctezuma or the children of Cortés? This question, long the central problem of Mexican historians, Justo Sierra answered by saying, "The Mexicans are the sons of the two peoples, of the two races ... to this we owe our soul."

Because Sierra recognized the dual parentage, he was able to view his country's history as an evolutionary process. Formed in both the indigenous past and the colonial past, the Mexican people, after three hundred years of slow and painful gestation, were finally born with the arrival of Independence. They came of age when the Reform, the Republic, and the nation achieved a single identity.

This classical synthesis, written on the eve of the Mexican Revolution, gave direction to the generation that furnished the Revolution's intellectual leaders. Although the author was Secretary of Public Instruction in the dictatorial regime of Porfirio Díaz, he was the first historian to show sympathy for the plight of the masses, and his book ends with the warning that political evolution has lost its way unless the result is freedom.

As Edmundo O'Gorman points out in an important essay on Mexican historiography, written especially for this edition, Sierra was also the first to write a history of his nation in a sincere endeavor to get at the truth, instead of shaping his account to prove a thesis or to preach some political faith. And yet, his work "owes its originality and its lasting merit to his vigorous interpretation of Mexico's history in the light of his convictions, of his keen insight, even of his fears." Though the chapters on the pre-Columbian Indian have been rendered obsolete by later archeological discoveries, the rest of the history is still valid and needs only to be brought up to date.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 426

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780292700710

- Date de parution :

- 01-01-66

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 152 mm x 229 mm

- Poids :

- 625 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.