- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

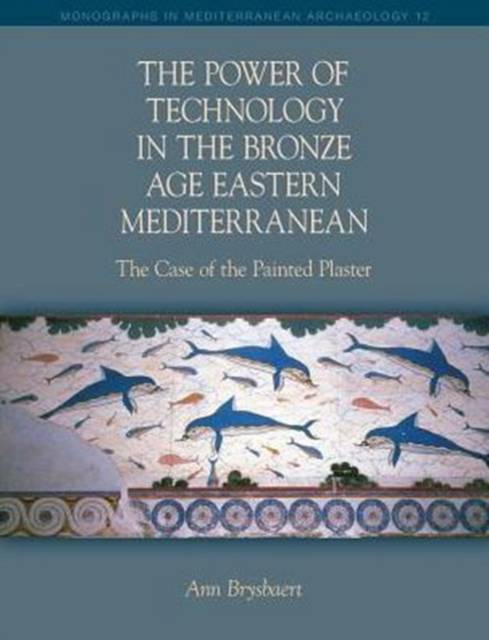

In the past, Bronze Age painted plaster in the Aegean and the Eastern Mediterranean has been studied from a range of different but isolated viewpoints. One of the current questions about this material is its direction of transfer. This volume brings both technological and iconographic (and other) approaches closer together: 1) by completing certain gaps in the literature on technology and 2) by investigating how and why technological transfer has developed and what broader impact this had on the wider social dynamics of the late Middle and Late Bronze Age in the eastern Mediterranean.

This study approaches the topic of painted plaster by a multidisciplinary methodology. Moreover, when human actors and their interactions are placed in the centre of the scene, it demonstrates the human forces through which transfer was enabled and how multiple social identities and the inter-relationships of these actors with each other and their material world were expressed through their craft production and organization.

The investigated data from sixteen sites has been contextualized within a wider framework of Bronze Age interconnections both in time and space because studying painted plaster in the Aegean cannot be considered separate from similar traditions both in Egypt and in the Near East.

This study makes clear that it is not possible to deduce a one-way directional transfer of this painting tradition. Furthermore, by integrating both technology and iconography with its hybrid character, a clear 'technological style' was defined in the predominant al fresco work found on these specific sites. The author suggests that the technological transfer most likely moved from west to east. This has important implications in the broader politico-economic and social dynamics of the eastern Mediterranean during the LBA. Since this art/craft was very much elite-owned, it shows how the smaller states in the LBA, such as the regions of the Aegean, were capable of staying within the large trade and exchange network that comprised the large powers of the East and Egypt. The painted plaster reflects a very visible presence in the archaeological record and, because it cannot be transported without its artisans, it suggests specific interactions of royal courts in the East with the Aegean peoples. The painted plaster as an immovable feature required at least temporary presence of a small team of painters and plasterers. Exactly this factor forms an argument in support of travelling artisans, who, in turn, shed light onto broader aspects of contact, trade and exchange mechanisms during the late MBA and LBA.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 286

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9781781792537

- Date de parution :

- 10-09-15

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 188 mm x 244 mm

- Poids :

- 703 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.