En raison d'une grêve chez bpost, votre commande pourrait être retardée. Vous avez besoin d’un livre rapidement ? Nos magasins vous accueillent à bras ouverts !

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

En raison de la grêve chez bpost, votre commande pourrait être retardée. Vous avez besoin d’un livre rapidement ? Nos magasins vous accueillent à bras ouverts !

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

14,95 €

+ 29 points

Description

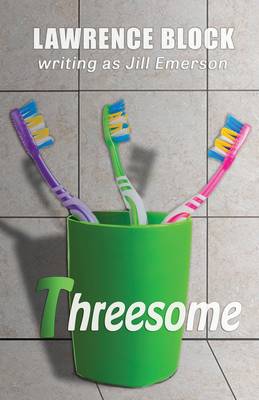

Jill Emerson, whose first three works were gentle explorations of the lesbian experience, took a sharp turn toward candor in THIRTY, her first book for Berkley. As I've explained in the book description for that novel, around the time Berkley came calling (via my agent) I'd become disenchanted with the whole notion of fiction recounted by some disembodied third- or first-person narrator. It struck me as artificial, and my response was to pile artifice upon artifice and produce a novel in the guise of an actual document.In THIRTY, the novel pretended to be a diary. That worked fine, and the resultant narrative proved at once challenging and effortless to sustain. I enjoyed writing it, Berkley enjoyed publishing it-and they wanted something else.What they got in THREESOME was a novel pretending to be a novel.The premise, as you'll see, is that the book has been written by its three main characters, Harry and Rhoda and Priss, in the form of a lightly fictionalized chronicle of their own life as a menage a trois. They set about writing alternate chapters-and, reading one another's work as they go along, they learn things they hadn't known, and one thing leads to another, and-I think the phrase we want is tour de force, and how nice to be able to use it in the same book description as menage a trois. The book was also about as much fun as I've ever had while sitting at a typewriter.I've written before about THREESOME, but there's something I've never recounted, and I'm old enough now to just go ahead and do it. Back in the early 1970s I had come in from rural New Jersey to hole up in a New York hotel and work on a book-this one-and after one evening after the day's work was done I drifted down to the Village and wound up in an establishment called the Kettle of Fish, on Macdougal Street. (It has since relocated to Christopher Street.) They serve strong drink there, and that night God knows they served more than enough of it to me. When I left I took a few steps and found myself in conversation with some folks in a car, a large station wagon, and they turned out to be six adolescent girls from the Convent of the Sacred Heart in Noroton, Connecticut, a very classy Catholic prep school. Their favorite teacher was driving, and the next thing I knew I was in the back of the vehicle with them.I guess they thought I was interestingly exotic, a drunk Bohemian writer indigenous to Greenwich Village. I in turn thought they were adorable. The teacher (an affable chap, but God only knows what he was about, and I'm sure in due course the school must have let him go) drove us back to Connecticut, and the rest of the evening was lost in nacht und nebel, as it were. I passed out on somebody's couch, woke up the next morning, and wound up taking the train back to the city with two of the young ladies. We went to my hotel room, where we may have smoked an illegal herb, and, um, necked a little.One of them saw my typewriter and asked what I was working on. I said it was a novel about a sexual relationship of two women and a man. Thoughtful pause. "I had no idea," she said, "that you researched these things so thoroughly."They left and I never saw them again, and if the incident rings a muted bell, it's probably because I used it as the opening of another novel, RONALD RABBIT IS A DIRTY OLD MAN, which masquerades as the collected correspondence of its protagonist. And which I'll be republishing fairly soon, but in the meantime we have THREESOME. It's a personal favorite of mine; that's no reason why you should like it, but I hope you do.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 212

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

- Tome:

- n° 5

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9781539543701

- Date de parution :

- 14-10-16

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 129 mm x 198 mm

- Poids :

- 213 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.