- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

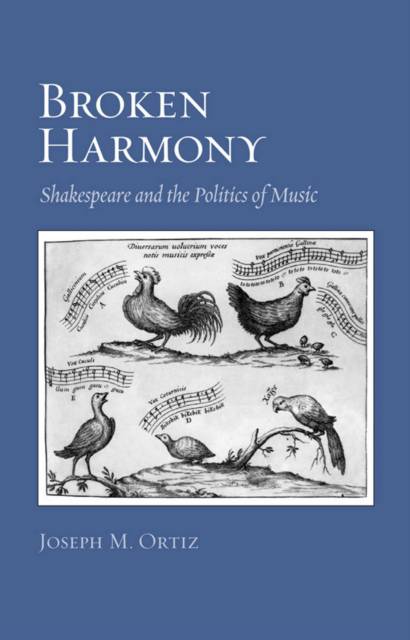

Music was a subject of considerable debate during the Renaissance. The notion that music could be interpreted in a meaningful way clashed regularly with evidence that music was in fact profoundly promiscuous in its application and effects. Subsequently, much writing in the period reflects a desire to ward off music's illegibility rather than come to terms with its actual effects. In Broken Harmony, Joseph M. Ortiz revises our understanding of music's relationship to language in Renaissance England. In the process he shows the degree to which discussions of music were ideologically and politically charged.

Offering a historically nuanced account of the early modern debate over music, along with close readings of several of Shakespeare's plays (including Titus Andronicus, The Merchant of Venice, The Tempest, and The Winter's Tale) and Milton's A Maske, Ortiz challenges the consensus that music's affinity with poetry was widely accepted, or even desired, by Renaissance poets. Shakespeare more than any other early modern poet exposed the fault lines in the debate about music's function in art, repeatedly staging disruptive scenes of music that expose an underlying struggle between textual and sensuous authorities. Such musical interventions in textual experiences highlight the significance of sound as an aesthetic and sensory experience independent of any narrative function.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 280

- Langue:

- Anglais

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780801449314

- Date de parution :

- 14-02-11

- Format:

- Livre relié

- Format numérique:

- Genaaid

- Dimensions :

- 163 mm x 236 mm

- Poids :

- 544 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.