- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

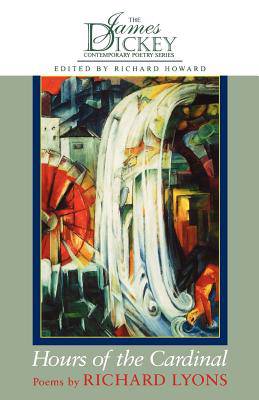

In Hours of the Cardinal, a mother's death triggers poems that journey through grief into the unnamable origins of consciousness--before thought, talk, even printed words. These elegies weave stories and anecdotes from literature and the visual arts, literally trying to cheat death by facing it, even facing it down. The ghosts that take flesh in this collection are poets such as Tsvetayeva, Mandelstam, and Tu Fu, painters such as Max Ernst and Kahlo, the mystic Henry Vaughan, the singer-dancer Josephine Baker.

By reprising these lives of exile and grief, the poems celebrate the body's attempt to endure in the face of historical atrocities, like the holocausts, racism, and the commodification of the human spirit. In the process of memorializing such lives, Richard Lyons fictionalizes his mother as one more member of the "great dead" as he levels the living and the dead by collaging autobiography and history into narrative meditations that carry the dignity of the individual against forces of greed and conformity.

But the literal decline of the body through age and illness finally forces these poems to invent a fictive afterair that ironically refuses any otherworldly solace. These poems trust Paul Eluard's famous lines "There is another world, / but it is in this one." In a long piece that merges some of the conventions of the elegy and the marriage poem, Lyons writes of "our ghostbody, / that part of us that hovers close to bliss."

In this book obsessed with death, things are always about to take shape and emerge; incipience and imminence are everywhere. The final section explores selfhood prior to its emergence into language and culture. In the poem "To My Deceased Mother," Lyons fictively reinhabits the body of his dead mother not to assume the innocence of the womb but to open some new territory prior to consciousness. Through his poetry Lyons bends time so that afterlife and prenatal consciousness become a single orbit.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 94

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9781570033216

- Date de parution :

- 31-03-00

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 138 mm x 214 mm

- Poids :

- 154 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.