- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

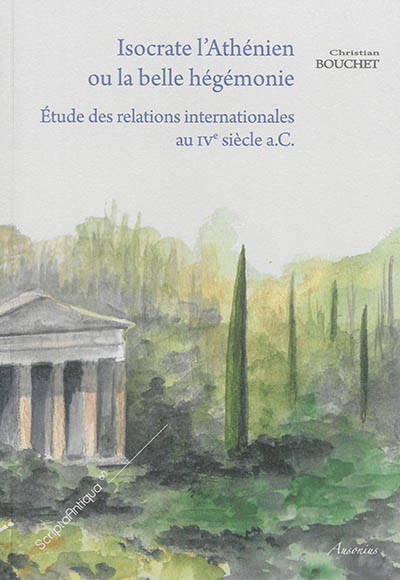

Isocrate l'Athénien ou La belle hégémonie

étude des relations internationales au IVe siècle a.C.

Christian BouchetDescription

Trop souvent et trop longtemps considéré comme un intellectuel de bureau,

éloigné de la tribune, Isocrate mérite très certainement une étude renouvelée,

tant sa pensée politique s'est affirmée, avec force souvent et avec subtilité

à l'occasion. Maître de rhétorique, d'abord proche des sophistes, Isocrate

a, durant sa très longue vie (436-338), assisté à nombre d'événements

qui devaient altérer ou réformer la démocratie athénienne (guerre du

Péloponnèse, dissolution de la ligue de Délos en 404/3 et création de la

seconde Confédération maritime en 378, guerre des Alliés en 357-355 et

ascension de Philippe II de Macédoine dans ces mêmes années 350). Bien

présents dans les discours et les lettres du rhéteur, tous ces faits s'ordonnent

en fonction de la question sans cesse posée de l'hégémonie athénienne.

Pour Isocrate, sa cité aspire légitimement à l'hégémonie, à la prééminence

en Grèce, face aux prétentions de Thèbes et surtout de Sparte ; et lorsque

les rapports de force deviennent franchement défavorables à Athènes, dans

les années 360-350, il envisage une autre forme d'hégémonie, distincte de

l'archè. Le vocabulaire de la domination militaire et politique laisse alors la

place à un registre plus politique et culturel. C'est ce glissement sémantique

qu'analyse le présent ouvrage, ponctué par une traduction nouvelle du Sur

la Paix (356/355).

We mistakenly use to see Isocrates as a bookworm, a man reluctant to speak

in public, but he actually deserves a new insight as far as he was asserting his

political thought with strength and a good sense of touch. Previously close

to the sophists, the teacher of rhetoric lived long enough (436-338) to be a

witness of so many events likely to alter of amend the Athenian democracy

(Peloponnesian War, dissolution of the Delian League in 404/3 and the

creation of the Second Athenian League in 378, the Allies' War in 357-355

and the rise of Phillip II in Macedonia in the 350'). Isocrates reported those

facts along all his discourses and letters, and he organized them according to

the continuous matter of the Athenian hegemony. Isocrates thought that the

hegemony of his own city and the superiority in Greece in front of claims of

Thebes or Sparta, were legitimate. Moreover, as soon as Athens was weaker

than those cities, around 360'-350', Isocrates began to look at another kind

of hegemony, different from the arche. In his works, it is no longer question

of military or political domination, but of a cultural one. This semantic

sliding of the word hegemony is the focus of this study, which offers a new

translation of the On the Peace (356/355).

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 277

- Langue:

- Français

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9782356131003

- Date de parution :

- 01-04-14

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Dimensions :

- 170 mm x 240 mm

- Poids :

- 560 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.