- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

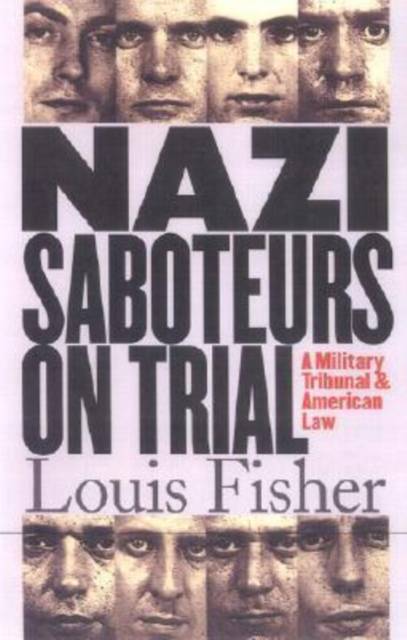

Silver Gavel Award, Finalist

Choice Outstanding Title

Although huge in scope and impact, the 9/11 attacks were not the first threat by foreign terrorists on American soil. During World War II, eight Germans landed on our shores in 1942 bent on sabotage. Caught before they could carry out their missions, under FDR's presidential proclamation they were hauled before a secret military tribunal and found guilty. Meeting in an emergency session, the Supreme Court upheld the tribunal's authority. Justice was swift: six of the men were put to death--a sentence much more harsh than would have been allowed in a civil trial.

Louis Fisher chronicles the capture, trial, and punishment of the Nazi saboteurs in order to examine the extent to which procedural rights are suspended in time of war. One of America's leading constitutional scholars, Fisher analyzes the political, legal, and administrative context of the Supreme Court decision Ex parte Quirin (1942). He reconstructs a rush to judgment that has striking relevance to current events by considering the reach of the law in trials conducted against wartime enemies.

Fisher contends that, although the Germans did not have a constitutional right to a civil trial, the tribunal represented an ill-conceived concentration of power within the presidency, supplanting essential checks from the judiciary, Congress, and the office of the Judge Advocate General. He also reveals that the trials were conducted in secret not to preserve national security but rather to shield the government's chief investigators and sentencing decisions from public scrutiny and criticism. Thus, the FBI's bogus claim to have nabbed the saboteurs entirely on their own was allowed to stand, while the saboteurs' death sentences were initially kept hidden from public view.

Fisher provides an inside look at the judicial deliberations, drawing on the 3,000-page tribunal transcript, Supreme Court records, and the private papers of the justices and executive officials involved. He analyzes the deep disagreements within the Roosevelt administration, leading to a conclusion in 1945 that the process used against the eight Germans had been defective and, thus, that an entirely different procedure was needed to prosecute two later German saboteurs.

Nazi Saboteurs on Trial also reveals just how poorly the justices resisted wartime pressures and how badly they failed to protect procedural rights. Although Ex parte Quirin is cited as an "apt precedent" by the Bush administration for the trying of suspected al Qaeda terrorists, Fisher concludes that the 1942 decision was, in the words of Justice Felix Frankfurter, "not a happy precedent." His book provides a sober cautionary tale for our current effort to balance individual rights and national security.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 216

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780700612383

- Date de parution :

- 22-04-03

- Format:

- Livre relié

- Format numérique:

- Genaaid

- Dimensions :

- 146 mm x 226 mm

- Poids :

- 403 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.