- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

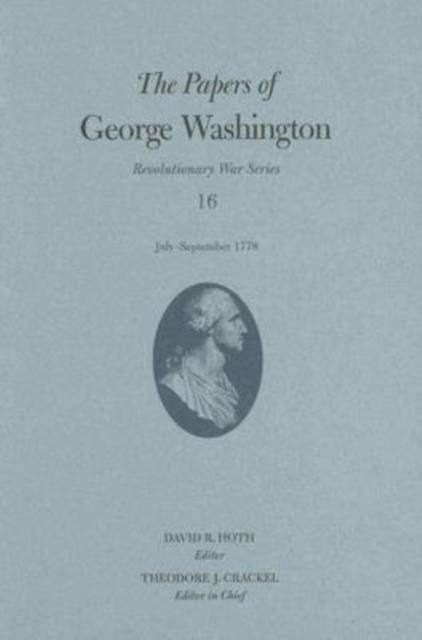

Volume 16 of the Revolutionary War Series documents the period from the beginning of July to mid-September 1778, a time of unusual optimism for Washington and his army. One of the first documents in the volume is Washington's detailed report to Congress of what was seen as a great victory at the Battle of Monmouth, and by July 11, the day on which Washington conveyed to the army Congress's congratulations on that victory, he received the welcome news that a French fleet had arrived in American waters. As it became clear that the fleet, commanded by the Count d'Estaing, was powerful enough to overawe even the British naval force then at New York, Washington, who understood the advantages usually afforded to the British army by their control of the seas, looked to deliver a decisive blow that might end the war. That aim meant he could do little in response to the destruction of the Wyoming settlement in western Pennsylvania and other rumblings of British, Tory, and Indian activity on the northwestern frontier. Washington's preferred option was to capture the main British army at New York City, so he moved his army to White Plains, where he would be in position to cooperate with the French fleet in operations against that city. However, he also prepared another option, directing Maj. Gen. John Sullivan, commanding in Rhode Island, to call up militia, ready magazines and boats, and gather intelligence for a possible assault on the British garrison at Newport. When d'Estaing reported that his ships were unable to enter New York harbor, Washington soon had a large detachment of troops and some of his best generals racing to join Sullivan in Rhode Island.As Washington, reduced to a spectator, pleaded for news, offered advice, and diligently gathered intelligence, the campaign opened with great promise. Sullivan's army marched to the British lines at Newport with little opposition, while the British destroyed their own ships at Newport to prevent capture by the French. But when Lord Howe brought his fleet from New York to challenge the French and d'Estaing sailed out to meet him, both fleets were battered by a massive storm that left the ships in need of repair. D'Estaing's decision to take his fleet to Boston for that work put the American army in a perilous position, especially as a fleet arriving from England strengthened Howe and returned control of the seas to the British. Although Sullivan's return to the mainland was accomplished safely, the expedition had failed.By mid-September, Washington's position was less promising than it had been in July. No longer planning offensives and speculating about a possible British withdrawal from America, he was instead using his best diplomacy to prevent the failed expedition from creating a rift in the French alliance. The initiative had returned to the British, whose intentions were not clear. As the volume closes, Washington has begun withdrawing his army to positions better suited to defense.

The editors of The Papers of George Washington were awarded a 2005 National Humanities Medal.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 800

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

- Tome:

- n° 16

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780813925790

- Date de parution :

- 06-10-06

- Format:

- Livre relié

- Format numérique:

- Genaaid

- Dimensions :

- 162 mm x 241 mm

- Poids :

- 1197 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.