- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

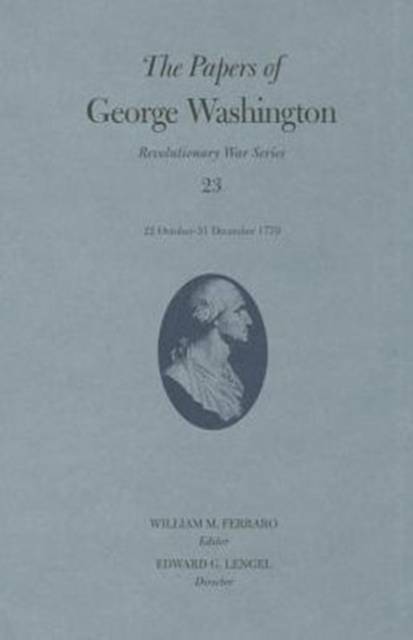

As October 1779 became November, George Washington realized that autumn had advanced too far for a combined Franco-American assault against the British forces in New York City that year, and he curtailed preparations. After a large British expedition departed New York in late December, Washington concentrated on settling his Army for the winter, which already had become unusually snowy and brutally cold. Troubles confronting the army and the incipient nation did not erode Washington's sense of humanity. When Elizabeth Burgin, a widow who had assisted American prisoners in New York City, called upon him for assistance, Washington ordered the commissary at Philadelphia to provide her with provisions and successfully urged Congress to extend additional relief. He also took careful measures to facilitate his wife Martha's travels fro Mount Vernon to join him at winter camp at Morristown. As British persistence, physical suffering among the troops, financial difficulties, and widespread disgruntlement eclipsed the optimism emanating from the enemy's evacuation of Rhode Island that October, Washington's personal fortitude and steadiness at this daunting time was crucial to the revolutionary cause.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 904

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

- Tome:

- n° 23

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780813936956

- Date de parution :

- 20-10-15

- Format:

- Livre relié

- Format numérique:

- Genaaid

- Dimensions :

- 170 mm x 241 mm

- Poids :

- 1451 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.