- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

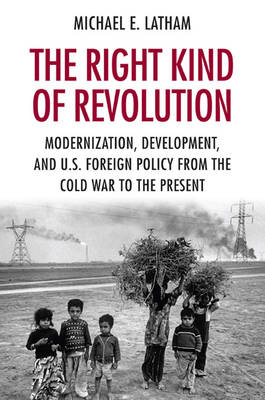

The Right Kind of Revolution

Modernization, Development, and U.S. Foreign Policy from the Cold War to the Present

Michael E LathamDescription

After World War II, a powerful conviction took hold among American intellectuals and policymakers: that the United States could profoundly accelerate and ultimately direct the development of the decolonizing world, serving as a modernizing force around the globe. By accelerating economic growth, promoting agricultural expansion, and encouraging the rise of enlightened elites, they hoped to link development with security, preventing revolutions and rapidly creating liberal, capitalist states. In The Right Kind of Revolution, Michael E. Latham explores the role of modernization and development in U.S. foreign policy from the early Cold War through the present.

The modernization project rarely went as its architects anticipated. Nationalist leaders in postcolonial states such as India, Ghana, and Egypt pursued their own independent visions of development. Attempts to promote technological solutions to development problems also created unintended consequences by increasing inequality, damaging the environment, and supporting coercive social policies. In countries such as Guatemala, South Vietnam, and Iran, U.S. officials and policymakers turned to modernization as a means of counterinsurgency and control, ultimately shoring up dictatorial regimes and exacerbating the very revolutionary dangers they wished to resolve. Those failures contributed to a growing challenge to modernization theory in the late 1960s and 1970s.

Since the end of the Cold War the faith in modernization as a panacea has reemerged. The idea of a global New Deal, however, has been replaced by a neoliberal emphasis on the power of markets to shape developing nations in benevolent ways. U.S. policymakers have continued to insist that history has a clear, universal direction, but events in Iraq and Afghanistan give the lie to modernization's false hopes and appealing promises.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 256

- Langue:

- Anglais

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780801477263

- Date de parution :

- 15-01-11

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 160 mm x 234 mm

- Poids :

- 367 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.